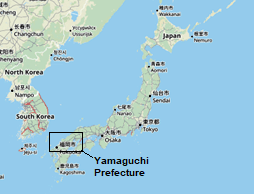

A trip in rural Japan, along rail lines with an uncertain future.

Closure in prospect

A few years ago, the Economist featured an article on the closure of some of Japan’s lesser used branch lines. It revealed that since 2000 a total of 44 railway lines, equivalent to a route mileage of 1,000km, have closed all over Japan. Another piece on the same subject appeared in the Railway Gazette in 2023 and suggested that one of the most common methods of closing rural railways was non-restoration after damage caused by significant weather events. Sadly, on a recent trip back to Yamaguchi, I was able to experience this new closure-by-stealth policy for myself.

Yamaguchi City

I had long harboured an ambition to travel on two rural lines in Yamaguchi Prefecture that looked particularly interesting to me; a ride on the Sanin Line from Masuda all the way around the sparsely populated north coast to Shimonoseki via Hagi, Nagato-Shi and Kogushi, and a trip along the Mine Line (pronounced “Me nay”) that links Nagato with Asa on the main Sanyo and Sanyo Shinkansen lines.

Yet in all the time I lived in Yamaguchi City (1988-1991) and on several trips back afterwards I have never got around to making either trip. Ironically, just as I began thinking I would finally have time to accomplish my goal during my next journey to Japan, both lines became impassable and now look likely to remain so in the future.

In June 2023 a serious storm caused extensive damage to both the Sanin line between Nagato-Shi and Kogushi and the Mine line south of Mine itself. The operating company, JR West, subsequently announced that all services would be replaced by buses and no plan for the restoration of the railways affected would be put in place.

I learned all this a few months before my departure from the UK. Disappointed, but not completely undeterred, I decided to make the most of things and at least try to travel on some of the parts of the lines that were still open. Not least because they too could come under threat in the future. Happily, my wife agreed to come with me.

Our plan was to start out from Yamaguchi-City and travel as far as Masuda on the Yamaguchi Line. Then, we would head back along the Sanin Line to Nagato-Shi. From there we would take a Mine Line replacement bus to Nagato-Yumoto for an evening stopover.

The next morning, we would continue on the Mine Line bus, change to the Sanyo Line at Asa and then head west to Shimonoseki.

We would return to Shin-Yamaguchi along the Sanyo Line and finally head back to Yamaguchi. It wasn’t the full railway circle that I had always intended, but it would have to do.

Yamaguchi to Masuda (Yamaguchi Line)

Our journey begins at Yamaguchi Station just after 9am on a cold Monday in February. This is my first visit back to the city since 2019 and I am a little shocked to see the station a bit worse for wear. It is now unmanned for much of the day, the little ticket office where I used to make reservations for the bullet train to Tokyo is long gone and even the 7-Eleven that used to be inside the building has closed.

The station first opened in 1913 when the 12km single track Yamaguchi Line reached the city from the junction with the Sanyo Main Line at Ogori (now Shin-Yamaguchi). The station building itself dates from 1978 and was thus only 10 years old when I first arrived here. The decline in usage figures, only 1,400 daily passengers now against 2,300 back then, tells its own story.

The station is decorated with posters advertising the Yamaguchi Line’s big claim to fame, the seasonal steam-hauled train “SL -Yamaguchi-go” which still makes the trip from Shin-Yamaguchi to Tsuwano and back. The train began operating in 1979, just three years after steam vanished in Japan, and has proved a big tourist draw ever since.

Today, we will be following the route of the steam train for the 50km to Tsuwano and then on for another 21km to the end of the Yamaguchi Line at Masuda. As we go out onto platform 3 we see a lot of passengers for the next service for Shin Yamaguchi. Meanwhile over on platform 1, there is hardly anyone waiting for the train we are planning to catch.

There are now only eight daily trains to Tsuwano and only six continue to Masuda. Our train is waiting at the platform. It is a single unit diesel Kiha 40, operated only by a driver. These units in one or two car formations were originally built between 1977 and 1979 and are used for all the local trains on the line. They are still in the same livery as they were when I lived here. Inside the train is immaculate.

We leave on time at 9:38 with just six other passengers apart from ourselves on board. For the initial part of the journey, we pass through the north of Yamaguchi City, making stops at Kami-Yamaguchi and Miyano. This part of the line sees more traffic especially with university and school students.

As we leave Miyano we begin the climb that will take us through the mountain range that separates the south, Sanyo, and north, San’in, sides of this part of Japan. At Niho there is a passing loop, and we encounter our first train going in the opposite direction, a Kiha 187 two-car unit forming the Yamaguchi line’s express “Super Oki” service heading for Shin-Yamaguchi.

There are three “Super-Oki” trains each way every day. This one has originated in Yonago in Shimane prefecture, but the other two come from Tottori. After Niho we enter a tunnel and emerge into thick woodland, the line now twists and turns and we go through several more tunnels as we climb.

We emerge from the forest for a stop at Shiome. At Chomonyko one of the passengers gets out. From the way he is dressed it seems that he is going hiking. Chomonkyo, an impressive gorge, is a local beauty spot. Sadly, the station was only used by around 11 passengers a day in 2020, so it would seem that most people access it by car.

The noise from the underfloor engine indicates that the gradient has slackened off a bit. We have now reached the mountain plateau, the line becomes straighter, and the scenery widens out. We continue on to Mitani where another single diesel unit heading for Yamaguchi is waiting for us to pass. Several of the stations on the line have passing loops, but only a few are still in use.

In April 2022, JR West Japan announced that the route between Miyano and Masuda Station was to be classified as “a line with a transportation density of less than 2,000 people per day.” What that means exactly for the future, beyond a call by JR for local government to do more to promote ridership, is unclear.

We make several stops, but no one gets on or off. The exact daily passenger usage figure quoted for 2017-9 between Miyano and Tsuwano was 566. This equated to a yearly deficit of 840 million Yen (around £4m). We reach Tokusa which, at 293m above sea level, is close to the summit of the line.

After Funahirayama we begin our descent. We twist and turn once more into dense woodland and pass through more tunnels. It is clear to see from the steep cuttings reinforced with concrete just how vulnerable a line like this is to landslides caused by violent thunderstorms.

In fact, almost the whole distance of the line we are travelling on from Tokusa down to the Tsuwano area was destroyed in a storm back in July 2013 and took almost 13 months to restore. I can’t help wondering that if the same thing occurred again now, immediate restoration might not be as forthcoming.

We emerge from the woodland having passed from Yamaguchi to Shimane Prefecture, and soon the picturesque town of Tsuwano (157m above sea level) can be seen. We are now treated to a vista looking down on the outskirts before coming down to a stop in the centre at 10:53. Four passengers get off. There is a scheduled pause of 15 Minutes here.

Ridership from Tsuwano has fallen from 2,237 people a day in 1987 to just 678 in 2019. At first, it seems that no one else will join us but with just a few minutes to go, an older gentlemen comes slowly down the station steps and boards the train. We leave at 11:08 precisely.

The situation at Tsuwano highlights the problems the railway faces. Much of it is probably down to depopulation, the number of people in Tsuwano has halved in the last 50 years, but there has also been an upsurge in the number of driving licenses over the same period, and this is particularly noticeable among the over-65 age group.

We make a couple more stops and at the second one, Nichihara, we gain an extra passenger; a young girl comes and sits opposite us. We are up to six.

We cross the Takatsu River and then follow it as it heads towards the sea, passing small tea plantations and making four more stops at empty platforms as we go.

Eventually we curve around to the right as we meet the Sanin Line from Nagato coming in on our left. Soon afterwards we arrive at Masuda, bang on time at 11:49.

Masuda to Nagato-Shi (Sanin Line)

The station layout at Masuda is the same as Yamaguchi, there is a main platform next to the station building and then two more on an island linked by a footbridge.

We are going to be boarding the 13:06 train to Nagato so we have a bit of a wait. The station seems a bit livelier than Yamaguchi, it is fully manned, and the convenience store is open. We decide to head into town for lunch.

Masuda is deadly quiet. Like almost everywhere else in Japan it is suffering from a declining population, down from 60,080 in 1985 to 45,000 in 2020. Eventually, we find a little noodle shop on the main street and enjoy a lovely lunch of soba (Japanese buckwheat noodles) with beef.

Back on the platform at Masuda station, we watch another single unit Kiha 40 leave the siding and come to a halt in platform 2. Ten minutes before departure and we get on board.

There are just three other passengers, a young girl in a school uniform, an older man and a guy who, if I am not mistaken, is a bit drunk. He slumps down on one of the seats and puts his feet across to the other side, unusual in Japan.

We set out along the Sanin Line, retracing our steps back to the junction with the Yamaguchi Line and then forking right across the River Takatsu. The 85.1km journey to Nagato-Shi is going to take us just under two hours.

We begin by hugging the coast, making a couple of stops before diving inland, passing through a tunnel and re-entering Yamaguchi Prefecture in the process. We cross the River Tama and stop again at Esaki where the drunk gets off.

The official name of this railway is the Sanin Main Line, it is actually 673km long and begins back in Kyoto. Sanin translates as “shady side” and refers to the Japan Sea Coast. No train traverses its full length and given that it is single tracked and unelectrified for much of the distance, the designation of “main” is a bit of a misnomer.

We continue inland through some very pleasant scenery with views of orchards, curve back to the coast again, cut across the base of a little peninsula in a series of long tunnels and then emerge back on the coast near Utago.

We continue our game of hide and seek with the coast, stopping at four stations as we go. All services on this section of the line between Masuda and Nagato are stopping trains, there are six a day doing the full trip and one extra one that terminates at our next station.

We arrive at Higashi Hagi (Hagi East), which serves Hagi, a town famous for its association with the movement that overthrew the samurai system and restored the emperor in the late 1860s.

We continue. We stop at three more stations as we follow the edge of a lagoon, and then back along the coast once more. We pause at Ii, which claims to have the shortest station name, in roman characters, in the world.

We make a brief pause at Nagato-Musumi, and then after another short run we curve around to the left as the 2km branch line from Senzaki appears on our right. We come to a halt at Nagato-Shi on time at 15:06.

Nagatoshi Station was opened almost exactly 100 years ago in March 1924. It serves the little town of Nagato which depends mainly on fishing and food processing for its livelihood, although there is now a fair bit of tourism thrown in.

Nagato used to be accessible by rail from 3 directions; from Masuda in the east, from Shimonoseki in the west and from Asa in the south. Now it is effectively at the end of a single branch line. In 1987 Nagato-shi was used by 1,741 people a day, by 2019 it was down to 478.

Nagato-Shi to Nagato Yumoto (Mine Line)

The Mine Line runs from Nagato-Shi down to Asa, a station on the Sanyo Main Line and the Sanyo Shinkansen. It is 46km long, not electrified, and has 10 intermediate stations. The trains used to take an hour to complete the journey, the bus takes just a bit longer. For much of the day, the replacement bus service from Nagato-Shi leaves at the same time as the train would have done.

For some reason, the replacement departure for the 15:14 train leaves at 15:09. That is just a three minute connection from the Masuda train. That is tight, even for Japan. As we emerge from the station building, I go to take a photograph of the bus, but as I do, it begins to leave. We shout to the JR employee who I realise I have just photographed telling the driver he can leave, and he manages to stop the bus.

As we clamber aboard, neither the driver nor the only other passenger, an elderly lady, seem impressed with us. The bus heads out of Nagato and onto the main Route 316, that it will follow most of the way to Mine. We make our first stop at Itamochi, opposite the closed station. No one is waiting. After a few more minutes we pull off the highway and twist through the little village of Nagato Yumoto to find the station.

Alighting from the bus, we make our way into the station. It is deserted but otherwise intact. Nothing about the waiting room suggests that there is no longer any train service. In fact, only 11 passengers a day used the station back in 2020, so it was probably deserted for most of the time even when the trains were running. We go out onto the platform. The railway has been out of use for only eight months, but it is apparent that nature is already starting to re-claim it.

We walk away from the station, almost parallel to the tracks and alongside the river that flows through the pretty little village of Yumoto. Yumoto is one of Yamaguchi’s most famous onsen (hot spring) resorts.

After a while, we pass over a level crossing near where the rusty rails of the Mine Line disappear into a tunnel. It looks totally intact here, but the effect from the storm last year is enormous and apparently there are 80 separate locations where damage has been done.

After a short walk we arrive at the Otani Sanso Hot Spring Hotel. It has a reputation as one of the best in Yamaguchi Prefecture, and we have been lucky to get a reasonable deal on a room; it helps that it is a Monday night of course.

We get a warm welcome from the reception staff, and there is a bonus, as we have used public transport to get here, we get a voucher worth 3,000 yen (£15) to spend on souvenirs or drink. We are shown to a beautiful Japanese style room with tatami mats and a balcony overlooking the river.

Before dinner there is a chance to go for a bath in the amazing hot spring complex on the lower floors. I spend a very enjoyable hour relaxing in a series of hot tubs both inside and outside.

Then, it is time for dinner. We enjoy a beautiful kaiseki seven course meal prepared with local ingredients including some of the area’s famous fugu puffer fish, the liver of which is poisonous and has to be removed carefully. When we return to the room, it has been made up with futons. A very relaxing sleep follows.

Nagato Yumoto to Shimonoseki (Mine Line / Sanyo Line)

The next morning the lovely people at Otani Sanso arrange a minibus to take us the 1km back to the station. We are not surprised to be the only ones waiting for the replacement bus. It comes on time at 10:08. There are six people on board and we don’t lose or gain anyone at any of the next three stops.

As the bus follows the course of the railway line down to Asa we get regular views of the empty track. Occasionally we come closer, meeting the rusty rails at level crossings.

Mine is the largest town on the line. It is also the busiest station, although it is down from 600 passengers a day in 2000 to just 272 now. Here we pick up our seventh passenger, a young lady with a suitcase. Although today the line runs through quiet countryside, there used to be limestone mining here, with a coalfield near Minami Omine, our next stop. As a result of this there used to be a fair amount of freight traffic on the line.

At Shirogahara, we pick up our eighth and last passenger. At Atsu no one gets on but there is a poster on the outside of the station building celebrating the 100th anniversary of the line in 2024. I wonder if they will ever restore it. Back in July 2010 it almost closed after storm damage, but it was eventually restored after 14 months. As we head out of Atsu we catch a glimpse of a damaged section in the distance; track sags over a gap where an embankment has been totally washed away.

Yunoto is the only one of the Mine Line stations the bus doesn’t call at. It is a bit out of the way and not easily accessible in a straight line from Atsu. JR offer a replacement taxi service instead. As we get off the bus at Asa a lady railway employee counts us. I suspect they are using the data to keep the railway shut or even to try to reduce the bus service.

Asa station is pretty impressive for the size of the town, with a new Shinkansen station being added to the existing building in 1999. Suddenly it feels as if we are back in the land of the “living railway”. There are quite a few people waiting for our Sanyo line train to Shimonoseki, and when it comes the 4-car electric unit is quite full.

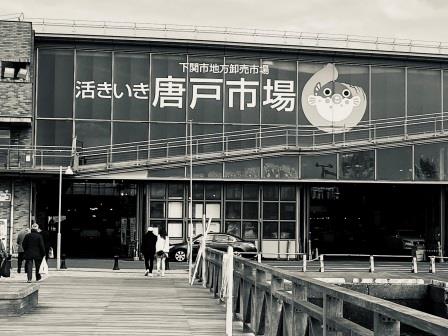

We arrive at Shimonoseki in time for lunch. Located right at the south western tip of Honshu, the city, with over 300,000 inhabitants, is the largest in Yamaguchi Prefecture. It is an important port, hosting ferry services to Pusan in South Korea.

The city is also an prominent fishing centre, it is nicknamed “fugu capital” and cartoons of the famous puffer fish can be seen everywhere. At the centre of everything is Karato wholesale fish market, which is also open to the public.

We spend a while walking around the stalls on the ground floor staring at tanks full of live fish. A lot of the action here takes place just after it opens at 5am, so it is pretty deserted by the time we arrive.

It is really the second floor we have come for. The sushi restaurant upstairs overlooking the market is famous for being both cheap and, given the fish is market fresh, absolutely delicious. It is very popular with the locals though, so we have to wait almost an hour to get a seat.

This is an old-style sushi restaurant where customers are supposed to pick plates as they pass in front of them on a conveyor belt, but the ordering process is now done by an iPad placed at each seat with the food delivered by a server, the revolving plates are now mainly for display. It is all amazingly fresh though, and some of the best sushi I have had in a long time.

Shimonoseki to Yamaguchi (Sanyo Line / Yamaguchi Line)

We return to Shimonoseki Station just in time for the hourly train back home. We retrace our steps along the Sanyo line to Asa and then continue onwards towards Shin-Yamaguchi making five stops. Although the passenger service on the line is only hourly at this time of day, there are a lot of freight trains passing in the opposite direction.

More than ten people change over to platform 2 at Shin-Yamaguchi where the four-car Yamaguchi Line train is waiting. It is already reasonably full. We depart on time at 15:39 and make brief stops at Suo Shimogo and Kamigo. At the second station the train fills with high school students on their way home from their studies.

Students are some of the biggest users of local trains in Japan these days. Small groups of them alight at the rest of the stations we stop at. We pass Nihozu, Otoshi, where there is a passing loop and another train waiting, Yabara and then the hot spring town of Yudaonsen.

Then finally we are back in Yamaguchi City. The little station perhaps belying the fact that the city is the prefectural capital and has a population of around 190,000. As passengers exit the station, the train prepares to turn around and head straight back to Shin-Yamaguchi.

With the section between Shin-Yamaguchi and Miyano still patronised by a relatively healthy 6091 people a day in 2019, it looks as if the future of this part of the line, at least, has a secure future. How much longer many other rural lines in Japan will be able to remain open for is another question.