Trips to Hokkaido and Nagasaki on bullet train lines that have yet to be fully completed.

Shinkansen Stumbling Blocks

When the British Government made the decision to curtail the “HS2” High Speed Line in late 2023, there was understandable criticism from many quarters. In some newspaper comment columns and in online forums people complained that other countries simply did not have the problems building key infrastructure projects that the UK did. Particular mention was made of Japan, home of the world’s first high speed line, the Tokaido Shinkansen, completed in five years and opened all the way back in 1964.

Yet, whilst it is true that Japan first linked its most important cities with high-speed trains many years ago, more recently the country has faced its own challenges with the construction of new lines. Of the four Shinkansen projects now either under construction or planned, only one has anything like a reliable finish date, and even that is six years into the future.

On a recent visit to the country, I travelled to the extremities of the bullet train network in an attempt to gain a little firsthand experience of the issues and problems involved. As a little bonus, I managed return visits to two of the most pleasant port cities in the country.

The Basic Shinkansen Plan

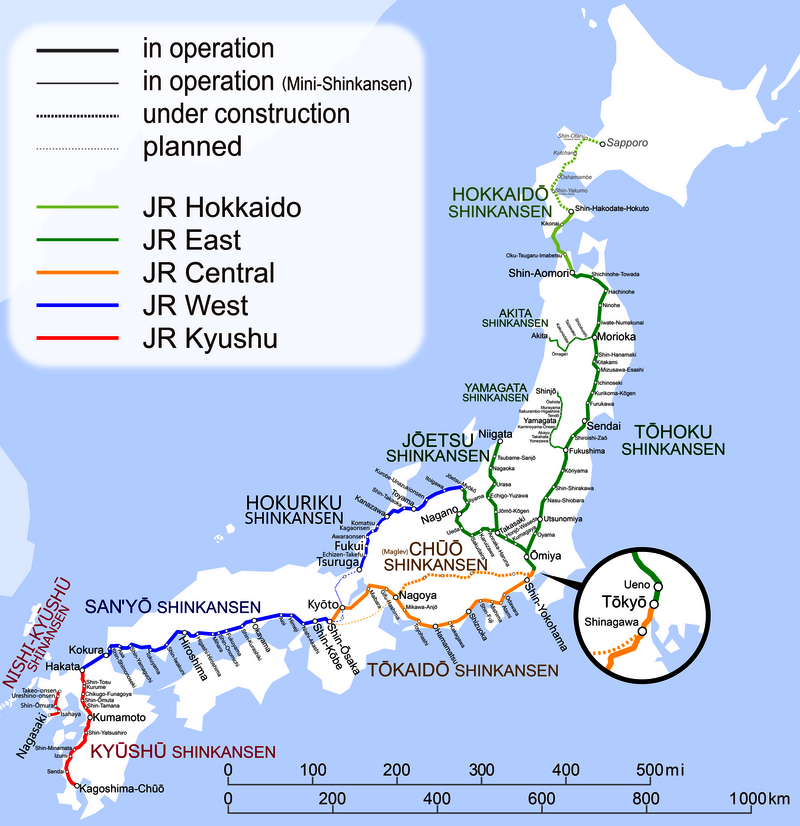

Back in 1973 the Japanese Government published a very ambitious development plan for a dense network of Shinkansen lines covering all of the country’s four main islands. The lines in the plan were divided into four basic categories: operational, under construction, planned and proposed. The lines are shown on the 1974 map below.

Operational lines are shown by a black & white line, the ones then under construction by two blue lines, those planned by a thin green line and the proposed routes by dotted brown lines.

The only lines operational back in 1974 were the original Tokyo to Shin-Osaka Tokaido Shinkansen (shown as A above) opened in 1964, and the Shin-Osaka to Okayama Sanyo Shinkansen opened in 1972.

Four lines were under construction in 1974; the Okayama to Hakata extension of the Sanyo Shinkansen (B) which would commence operations in 1975, the Joetsu Shinkansen (C) to Niigata and the Tohoku Shinkansen (D) to Morioka which would both open from Omiya in 1982 and later be extended to Tokyo by 1991. The Narita Shinkansen (E) to Narita Airport would later be cancelled due to land purchase issues.

Of the five “planned” lines in 1973, two have now been fully completed. The Kyushu Shinkansen (1) from Hakata to Kagoshima was finished in 2011 and the extension of the Tohoku Shinkansen* (3) from Morioka to Shin-Aomori was completed in 2010.

*Branching off from the Tohoku Shinkansen are also two so-called “mini shinkansen” lines serving Yamagata/Shinjo (1992/1999) and Akita (1997). The concept uses conventional lines with widened (1435mm) track to accommodate Shinkansen trains. The trains, which run through from the Tohoku Shinkansen, have narrow car bodies to fit the tunnels and bridges of the converted lines. Maximum speed on the branches is limited to 130km/h.

Delayed Progress

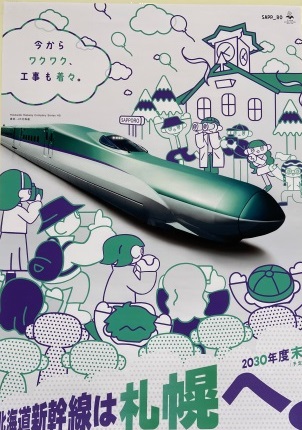

Progress with the other three lines planned in 1973 has been a lot slower and none of them is yet fully complete. The Hokkaido Shinkansen (5) was completed to Shin-Hakodate Hokuto in 2016 and is now under construction to Sapporo but with a proposed opening date of 2030/2031.

The Hokuriku Shinkansen (4) was completed to Nagano in 1997 and was initially known as the Nagano Shinkansen. It was extended to Kanazawa in 2015. In March 2024 it reached Tsuruga, but final completion to Shin-Osaka is not now forecast before 2045.

A short section of The Nishi Kyushu Shinkansen (2) was completed between Takeo Onsen and Nagasaki in 2022 but the line is not expected to reach Hakata any time in the near future.

Meanwhile, of the many lines ambitiously proposed in 1973 only one made it through the planning process. The Chuo Shinkansen (6), now using linear motor technology, is scheduled to open between Tokyo and Nagoya sometime in the 2030s, whilst there is no date yet for the start of construction of the Nagoya to Shin-Osaka section (7).

Problems of land purchase, environmental concerns, complex political issues and budget over runs have all conspired to mean that the basic network planned back in 1973 will take almost 70 years to complete.

Included below is a review of the four outstanding projects, including my recent trips on the Hokkaido Shinkansen from Tokyo to Hakodate and the Nishi Kyushu Shinkansen from Hakata to Nagasaki.

1. Hokkaido Shinkansen – “Noise, Speed and Distance”

My first journey began at Tokyo just after 8am on a Saturday morning in February. I boarded the 08:20 Hayabusa express heading for Shin-Hakodate Hokuto. The sleek long nose of the E5 type, operated by JR East, testified to the fact that this was the country’s fastest bullet train.

The Hayabusa, like all the trains running onto the Hokkaido Shinkansen, was reservation only. I had only made my booking a couple of days before, but I still managed to bag a window seat. As we left Tokyo, I saw that the train was far from full.

The various speeds attainable on the Tohoku Shinkansen are testament to some of the issues with the line’s construction. Originally opened in 1982 from Omiya, 31km north of Tokyo, to Morioka, the line was extended back to start first from Ueno in 1985 and then finally from Tokyo itself in 1991.

Limited to 130km/h as far as Omiya, we made a comparatively slow start through the urban sprawl. At one point we ran parallel to the Saikyo commuter line which was built back in the 1980s as a sop to local residents who had protested against the bullet train tracks. When the Tohoku Shinkansen project was first announced activists mounted a series of sit-ins and demonstrations to try to impede its construction south of Omiya.

Beyond Omiya we sped up, first to 275km/h and then beyond Utsunomiya to the maximum 320km/h. The ride was smooth, but it looked cold outside with plenty of snow lying on the ground. Having made stops at Omiya and Sendai we reached Morioka (almost 500km from Tokyo) at 10:31.

Morioka was the 1982 terminus, and it was to be another twenty years before the line was extended on to Hachinohe in 2002 and finally to Shin Aomori in 2010. As we accelerated away from Morioka the speed was noticeably slower. For the rest of our journey, although we were travelling on lines that opened quite recently, we never exceeded 260km/h.

The reason for the dramatic speed drop is because noise abatement laws passed in the 1980s limit the operating speed of all newly built Shinkansen lines. Noise pollution law suits first began after the Tokaido Shinkansen was completed in the 1960s with the first complainants being residents near the line in Nagoya. Bizarrely the new legislation has never been applied to the already-built lines. This means that trains are free to speed up to 320km/h on the 1982-built stretch to Morioka, and there are now even plans for faster ones to reach 360km/h.

We reached Shin Aomori at 11:18, having covered the 675km (419.4 miles) from Tokyo in just under three hours. From this point onwards the train passed on to the Hokkaido Shinkansen and into the care of JR Hokkaido. I noticed that there was a crew change, but even more apparent was a reduction in the number of passengers. When we got underway again there were fewer than ten people in my carriage. This is in line with reports that say that occupancy rates sink to around 20% or less in February.

The train made rapid enough progress after leaving Shin Aomori but eventually slowed as it passed through Oku-Tsugaru-Imabetsu station on the approach to the Seikan Tunnel which would take it under the Tsugaru Strait to the island of Hokkaido. Construction of the 53.85km tunnel was commenced in 1971 and it opened to narrow gauge traffic in 1988. I made my first trip through it the year after.

The tunnel was always designed for Shinkansen trains, but the network took 28 years to link up with it. Finally in 2016 it was modified to dual gauge to accommodate the bullet trains. Although no narrow gauge passenger trains now traverse the tunnel there are still approximately 50 daily freight trains. The danger of these derailing due to the shock wave of the faster bullet trains limits the Shinkansen to 160km/h through the tunnel, although 260km/h is allowed on holidays when no freight is running.

We emerged from the tunnel into the daylight of Hokkaido. After passing through Kikonai we briefly sped up again before finally coming to a halt at Shin-Hakodate Hokuto at 12:17. It had taken us 3 hours 57 minutes from Tokyo, but an hour of that had been used up in covering the final 148km. Visible from the station was the first tunnel on the next section of line that is now under construction, stretching 212km towards Sapporo and expected to open in 2030 or 2031.

The city of Hakodate itself is located at the bottom of a peninsula, and whilst the conventional line headed there to a terminus, the Hokkaido Shinkansen, aiming for Sapporo, bypasses it. Shin-Hakodate Hokuto actually lies around 18km to the north of the city in sparsely populated countryside. From here one can make a 3 hour 30 minute journey by conventional train on to Sapporo or a 15 minute ride into the city itself on the Hakodate Liner train.

It seemed most of the passengers who alighted from the Hayabusa followed me onto the 12:35 Liner, but when the train finally came in and we all got on board I noticed that even though it only had two carriages there was no one standing. Currently only around 1900 passengers a day use Shin-Hakodate Hokuto, whilst the two intermediate expensive-looking stations we passed through on our way from Shin-Aomori have less than 60 daily users.

The Liner pulled up at Hakodate station at 12:50, the full journey had taken 4 hours and 30 minutes from Tokyo, and although the service runs roughly every hour, it is hard to see why many people would use it over the option of flying. The journey time issue could pose problems for the Hokkaido Shinkansen even after its completion to Sapporo. The initial transit time from Tokyo is forecast to be around 5 hours. JR Hokkaido have put in a request to run some of the new sections at 360km/h but even if permission is granted and the target 4-hour journey time is reached, it may still be too slow to lure many passengers from air.

A few hours in Hakodate

It had been over thirty years since I had last visited Hakodate. The city (population: 239,000) was Japan’s first port to be opened to foreign trade in 1854 and has a slightly distinctive “western” feel about it that is found in other similar cities such as Yokohama, Kobe and Nagasaki.

2. The Hokuriku Shinkansen – “A difficult choice of routes”

Like all other lines completed since the 1990s, the Hokuriku Shinkansen is constrained by a line speed of 260km/h for the whole of its length between Takasaki on the Joetsu Shinkansen and its current terminus of Tsuruga. Nevertheless, completion of the line to Nagano in 1997 and a further extension to Kanazawa in 2015 boosted travel to these destinations and can be seen as a big achievement.

The value of the final stretch on from Kanazawa to Shin Osaka, of which the first section to Tsuruga opened in March 2024, is less obvious. The latest extension gives Tsuruga (population: 64,000) a journey time of around three hours from Tokyo, which is no real improvement on using the conventional line (shown in yellow below) to Maibara and the Tokaido Shinkansen on from there.

The eventual goal to link Kanazawa and Toyama to the Kansai area might seem laudable, but the route of the final section from Tsuruga to Osaka has been mired in controversy for years. Five different plans were at one time under consideration, with the planned route via Obama and Kyoto only being finalised in 2016.

The route chosen is the most expensive and it means the line will go through sparsely populated areas before reaching Kyoto where, in a decision which is already creating protests, it will tunnel under the city to a new and very expensive underground station. Access to Shin-Osaka will also be in a tunnel. In any case, environmental assessments and budget constraints mean that it will be 2030 before construction begins and 2045 before the line finally opens.

3. Nishi Kyushu Shinkansen – “An embarrassing gap”

My second trip began at Hakata a few days later. I boarded JR Kyushu’s 10:04 Kamome express which according to the departure boards was heading for Nagasaki. In fact, it was the “Relay Kamome” and it would take me along the conventional line only as far as Takeo Onsen from where I would need to catch a bullet train, also branded as Kamome, for Nagasaki.

My train was a Class 885 unit of the type which used to make the whole journey to Nagasaki along the conventional line in 1 hour and 55 minutes. Now, the combination of “relay” and bullet train would take me 1 hour 20 minutes although most trains in the schedule still take around 1 hour 30 minutes.

I like the Class 885, and like many of the trains operated by JR Kyushu it has a quirky interior which still feels quite fresh despite it now being 20 years old. This is down to the work of designer Mitooka Eiji who has been collaborating with the company for many years and is also responsible for the look of the new N700S Kamome bullet trains.

We departed on schedule and followed the conventional line out through the Fukuoka suburbs towards our first stop at Tosu, unfortunately picking up a 4 minute delay in the process. At the next stop, Shin-Tosu (30km), we intersected with the Kyushu Shinkansen on its way from Hakata to Kagoshima. We were scheduled to reach Shin-Tosu in 23 minutes, the bullet trains following a more direct route, partly in tunnel, can make it in 13.

As we left Shin-Tosu behind, I glanced at the Kyushu Shinkansen tracks heading south; presumably if the rest of the project to Nagasaki ever gets built, the new line will curve around from a junction here and then somehow, parallel to the current route, follow a course to Takeo Onsen some 50km away.

That this missing gap shows no sign of being plugged any time soon is down to the opposition of local politicians in Saga, the prefecture through which I was passing. Unwillingness to fund any of it, and unconvinced about the benefits to themselves, they have consistently blocked proposals. As it stands at the moment no route has been decided, no plan is on the table and no construction has been scheduled. The future of the Relay Kamome seems assured for now.

After twenty minutes we made a stop at Saga City and then after another twenty minute run, arrived at Takeo Onsen still four minutes behind our 10:58 scheduled arrival time. A N700S type Shinkansen decorated in Mitooka’s innovative livery was waiting in the platform opposite. The disciplined Japanese passengers were quick to make the swap between the trains. It was all completed well within the scheduled 3 minutes, and soon we were off again.

I wandered through the train checking out the impressive interior styling. In theory this train is identical to the N700S units now being used on the Tokaido and Sanyo Shinkansen lines, but inside it felt quite special. The Relay Kamome had seemed quite full, but the greater capacity of the bullet train meant people spread out and it seemed almost empty by comparison.

I was travelling on one of the line’s four six-car trains. They are maintained at a depot near the midpoint of the route, and unless the line is extended they will remain isolated from the rest of the Shinkansen system.

Predictably, we were often in tunnel but the views from the short sections out in the open were pretty impressive, although I missed the old route which used to hug the coast as it wound its way around the peninsula that we were now cutting through the middle of.

The Nishi Kyushu Shinkansen is only 66km long, the shortest bullet train line in Japan, but it still has three intermediate stations. Most services, which operate on a sometimes half hourly, sometimes hourly pattern, call at all three stations, and running at the line’s 260km/h maximum, take 30 minutes end to end. Our own train was scheduled to skip through the first two stations and call only at the last one, Isahaya.

Finally, we slowed down and as we emerged from our last tunnel the familiar sight of Nagasaki came into view. My journey from Takeo Onsen had taken the scheduled 23 minutes, although unfortunately we were still four minutes down on the schedule.

The new station at Nagasaki was very impressive. The Shinkansen has two elevated island platforms serving four tracks, which at the moment looks like hopeless over provision. The conventional part of the station also has two island platforms but here there were five tracks.

If the gap between Takeo and Shin Tosu is ever closed, the whole journey to Hakata should come down to around 50 minutes, with trains presumably being extended along the Sanyo Shinkansen towards Shin-Osaka. Whether that day will ever come or not remains a big question.

It would also seem that not everyone in the city is keen for it to happen. Nagasaki (population 390,000) has one of the fastest falling populations in the country and having Fukuoka, one of the only growing cities, less than an hour away would, based on evidence elsewhere, merely serve to accelerate the decline.

A few hours in Nagasaki

The area outside Nagasaki station had undergone extensive redevelopment too and there was an impressive Marriot Hotel in part of the complex. Elsewhere, the city seemed largely unchanged from my last visit several years ago. It rained the whole time I was there.

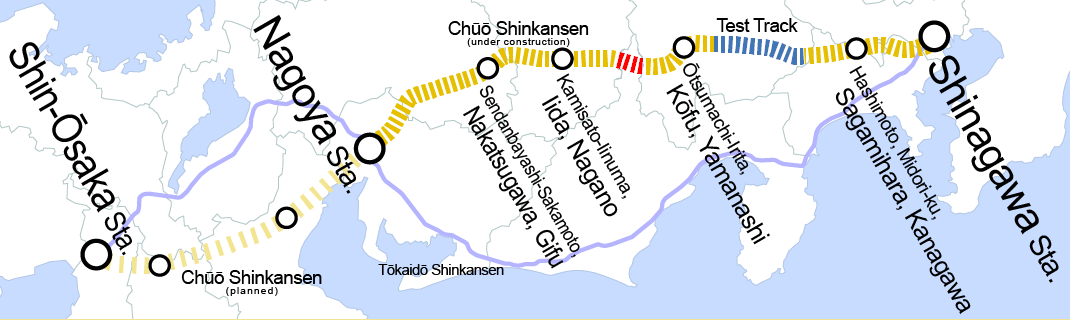

4. The Chuo Shinkansen – “Water and Politics”

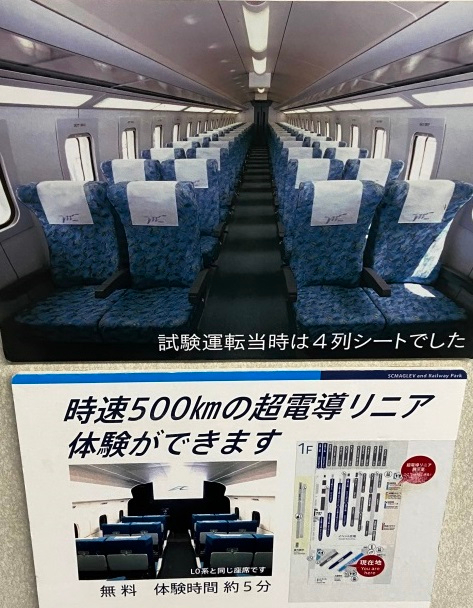

The Chuo Shinkansen will utilise maglev technology and this, along with the fact that about 90% of the 286-kilometer (178 miles) line from Tokyo to Nagoya will be in tunnels, means it will not be subject to the restriction to 260km/h of other new lines. In fact, it will operate at a speed of around 505km/h and reduce the journey time from Tokyo to Nagoya to a highly impressive 40 minutes. If a further extension is built, it is expected to reach Osaka in 67 minutes against the 2 hours 30 minutes it takes today.

Yet, the line, to be operated by JR Central, has its own problems. Construction is yet to commence on a central section that passes through Shizuoka Prefecture. Local government has expressed concern about water from the Oi River getting into the tunnel and reducing water levels. This has given rise to the seemingly bizarre situation where delay in constructing around 10km of line (shown in red below) is now throwing the whole project off schedule for years.

Cynics believe that the Prefectural government are angling for concessions, among which is the construction of a new station on the Tokaido Shinkansen to serve Shizuoka Airport. In any case, the refusal of officials from Shizuoka Prefecture to authorise construction work has so far meant that the planned date for opening the line has moved from 2029 to the mid-2030s.

End of the line?

The Chuo project has been pilloried by many on cost and energy consumption grounds. The question over its economic justification, with its opening date scheduled to coincide with a period when Japan’s population is scheduled to shrink even faster and when very possibly modern technology could render the need for a lot of business travel obsolete, actually applies to all the Shinkansen projects not yet completed.

With the exception of Sapporo, Japan’s bullet trains now serve all cities that have populations of more than a million. The country has successfully used the strategy of high speed line construction to boost economic development, but as plans get increasingly costly and the economic benefits become less clear amongst changing demographics, the country is starting to reevaluate things. As the UK struggles to get started on its own high speed network, it might be time for Japan to finally stop.