Visiting Bulawayo and its railway museum

The Plan

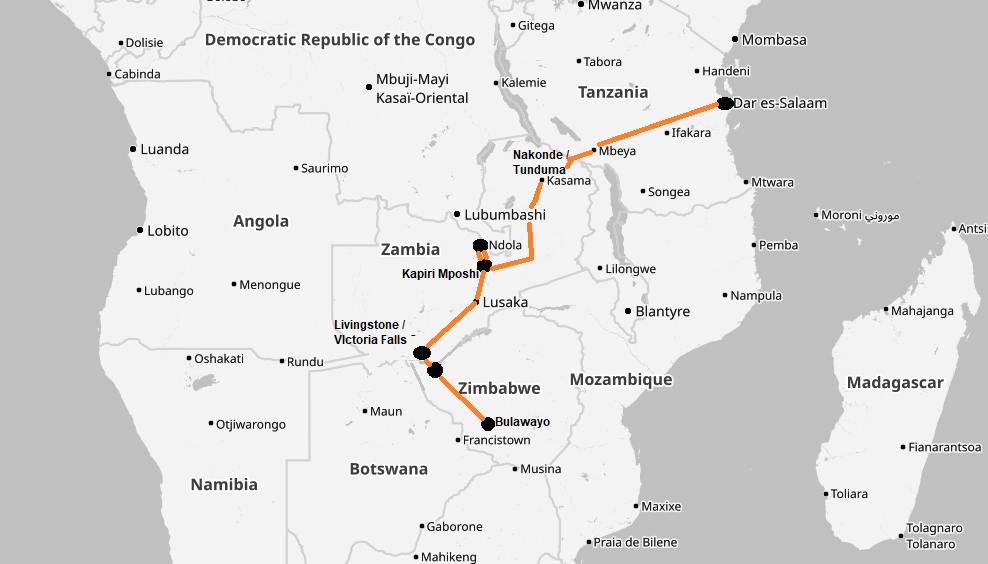

In late February 2025 I travelled to Bulawayo, Zimbabwe’s second city. After visiting the railway museum there, I planned to embark on an overland journey of around 3000 km to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. I would follow the route of the “Cape to Cairo” Railway to Ndola in Zambia before doubling back to Kapiri Mposhi to follow the “Tazara” Railway across the Tanzanian border and on to Dar.

I had allocated more than a week to finish this trip and I aimed to complete as much of it as I could by train. My timing was less than perfect though, a series of recent disruptions and longer-term problems meant that even before I left Bulawayo, I knew that I would be experiencing a fair amount of bus travel too.

The Railway Museum

I flew out to Zimbabwe on Ethiopian Airlines, enjoying a stress free journey and managing to include an interesting stopover in Addis Adaba. Entry into Zimbabwe was relatively expensive, they charged $50 for an e-visa which was obtainable on line in advance, but otherwise the immigration process was smooth and friendly.

My first stop after arriving in Bulawayo was, perhaps unsurprisingly, the railway museum, located just south of the main city centre. It had long been on my “bucket list” and it did not disappoint. More than twenty steam and diesel locomotives along with various carriages and wagons combined with informative displays and other memorabilia to tell the story of how railways changed the history of this part of Africa.

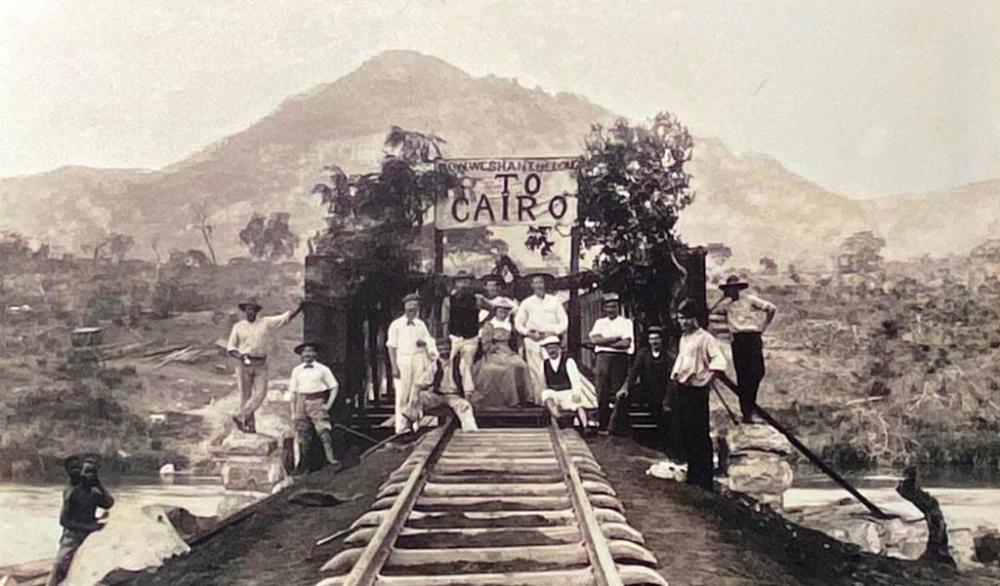

The private coach used by Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902) was one of the most famous exhibits on display. Rhodes remains a highly controversial figure but his part in the plan for a railway line stretching all the way from Cape Town to Cairo, helped to shape the railway networks of both Zimbabwe and Zambia.

The private coach used by Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902) was one of the most famous exhibits on display. Rhodes remains a highly controversial figure but his part in the plan for a railway line stretching all the way from Cape Town to Cairo, helped to shape the railway networks of both Zimbabwe and Zambia.

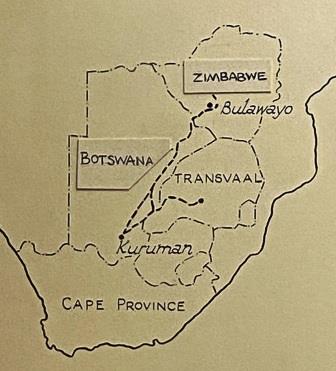

The railway reached Bulawayo in 1897, travelling via present-day Botswana to provide a link from Cape Town. Construction then started on continuing the line northwards towards Cairo. By 1909 it had been extended through Victoria Falls, Livingstone and Lusaka to arrive at Ndola in the north of present-day Zambia.

The line then crossed the border into what was then Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) where, after a few hundred miles, it eventually ended well short of its Egyptian goal. Despite the fact it terminated short, the completed sections within Botswana, Zimbabwe and Zambia are still often referred to as the “Cape to Cairo” Railway. It was part of this route that I planned to follow.

Links

More information on the Cape to Cairo plan

Rhodesia / Zimbabwe’s Railway History / (& Railway Museum)

The Bulawayo Club

I had been lucky enough to get a good deal on a room at the Bulawayo Club. Situated right in the central business district, the building dates from 1934 although the club itself, which apparently still functions, began back in 1895.

The whole place was beautifully appointed and featured a snooker room, library and bar. In the centre was an outdoor atrium, the perfect place to enjoy the full English breakfast included in the room rate. The service was friendly and welcoming.

I was a little surprised to find that they seemed to have kept the trappings of old Rhodesia here. It was as if time had stood still. There was a photograph of a young Queen Elizabeth, small portraits of various colonial dignitaries and a larger one of Rhodes himself. It all seemed just a little odd, especially given the Mugabe regime’s well publicised denouncement of all colonial influence.

On my first night in town, I chose to eat at the Bulawayo Club. I chatted with the guy behind the bar for a while and he told me about his experience moving from his village a hundred miles away, explained the local football league to me and suggested things in Bulawayo and the country itself were now improving a bit.

I did a bit of research on my own. Zimbabwe had a population of 17 million of whom 84% were Christians. The country had 16 Languages, but in Bulawayo (population 600,000), the most prominent language was Ndebele. Shona was also spoken but English served as a lingua franca across the country. The Zimbabweans drove on the left (as would the Zambians and the Tanzanians) and most places used the British style plug, although at the Bulawayo Club there were only older South African style sockets available. I had to borrow an extension lead with a converter.

Zimbabwe had a theoretical annual GDP per capita income, when adjusted by purchasing power parity (PPP), of around $2,250. The country’s problems with corruption, economic mismanagement and hyperinflation are well known. Although a new currency, the Zimbabwean Gold, was introduced in 2024 well over 70% of all transactions in the country were still in United States Dollars in early 2025. Certainly, I never saw any local currency and all my own dealings were all in dollars.

City Hall

I enjoyed walking around the centre of Bulawayo. I found the mixture of old colonial buildings, 1950s architecture and wide streets fascinating. For some reason, I was not quite sure why, It reminded me a little bit of being in Australia back in the 1980s.

Bulawayo was founded in the 1840s and it was ruled by Ndebele King Lobengula from the 1860s. The tribal history is evidenced in the name itself which comes from the Ndebele word bulala meaning “the one to be killed.”

In 1893, during the First Matabele War, soldiers from Rhodes’ British South Africa Company (BSAC) invaded. Lobengula set fire to his capital and fled. BSAC troops and white settlers then occupied the ruins and created a new town. Bulawayo officially became a municipality in 1897.

Walking around the wide streets with their central parking bays today, you might think they were designed with the motor car in mind, but apparently the width of the streets resulted from the need to turn a cart pulled by up to sixteen bullocks around.

Bulawayo quickly developed into an industrial hub and administrative centre. Standing in front of the city hall, admiring its lush gardens, elegant facade and imposing clock tower today, you can easily imagine that this place became successful quite early in its development.

The informal economy

The city centre seemed vibrant but also quite relaxed. People were exchanging smiles with each other and with me. I stopped once or twice to check directions and each person I met was helpful and friendly.

In some places, the city centre seemed a little down at heel, with some of the shops shuttered up, but there was also a very modern arcade full of people shopping or just relaxing. It seems the economy might just be recovering after years in the doldrums: Zimbabwe is on course for 6% growth in 2025.

In some places, the city centre seemed a little down at heel, with some of the shops shuttered up, but there was also a very modern arcade full of people shopping or just relaxing. It seems the economy might just be recovering after years in the doldrums: Zimbabwe is on course for 6% growth in 2025.

Nevertheless, there was certainly a lot of evidence of the “informal economy” that makes up around 64% of the total Zimbabwean economy (one of the highest rates in the world). There were vendors everywhere selling on the pavement in front of shops.

In the centre, these traders seemed to be complimenting the open shops, fruit vendors standing in front of a KFC outlet for example. But the further out of the centre I walked, the more closed down shops there seemed to be and the street traders were far more prevalent.

The level of unregulated trading obviously indicated there were significant social problems in the background. Looking online, it seemed the city is trying to do something to formalise these street vendors, perhaps providing them with more stable permanent environments in which to trade.

The Selborne Hotel

I had heard that Bulawayo was supposed to be a good town for pubs and I made sure I sampled a few of them. I started off with a bottle of Castle lager at the Skittle Inn near the railway station and was engaged in friendly conversation about what I was doing in the city.

Then I called in at the Selborne Hotel in the centre of town, busy on a Saturday afternoon with people watching English football on the TV. A lot of people I encountered seemed to be wearing English football shirts and the Premier League was an easy starting point for conversations. One of the guys I got chatting to turned out to have a relative in the UK and we managed to call him on WhatsApp and say hello.

The Natural History Museum

Bulawayo is also home to what some claim is Zimbabwe’s best museum, the Natural History Museum. I certainly enjoyed the couple of hours I spent there, although I thought it probably could do with a bit of investment and updating.

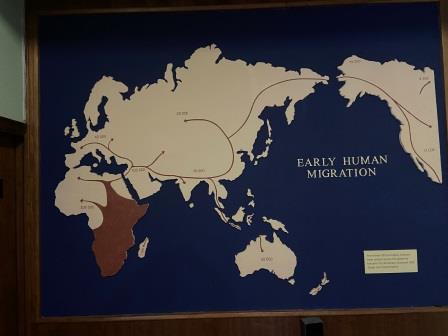

The ground floor had reasonable, if a little dated, displays of African wildlife including the second largest stuffed elephant in the world. The story of the development of the human race on the continent and its spread around the globe was also very well presented.

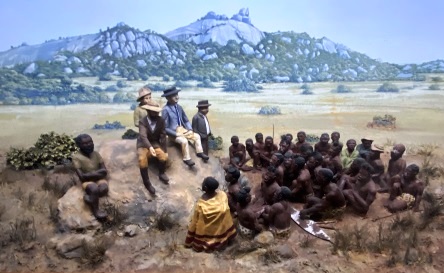

On the upper floor there were some interesting exhibits on the history of local peoples, Lobengula and the establishment of Bulawayo, but nothing really on the impact that white settlement had on the Indigenous people and still less on how Rhodesia became Zimbabwe.

The history section seemed to be presented from a Eurocentric point of view, possibly because the museum has not been updated much since it opened in 1964. Certainly, a concentration on the stories of the white settlers seemed a little out of place in modern Zimbabwe.

Walking through Centenary Park, on my way back from the museum, I came across a memorial to a BSAC officer killed in the first Matabele war in 1894. Just as at the Bulawayo Club, it seemed a little odd. Wouldn’t the perception be that this was a powerful symbol of colonialism and racism and it should be removed?

I suppose the argument would be that destroying it does not change the history, retaining it helps tell the story, perhaps? It is obviously a complex and multi-faceted issue. In contrast, the statue of Cecil Rhodes that used to stand in the city centre had been removed and replaced with a statue of Joshua Nkomo, a prominent figure in the liberation struggle. Here they had kept the historic plinth but replaced the figure.

The Railway Station

I could easily have stayed in Bulawayo for a few more days, but the problem was that my itinerary depended on catching a couple of trains that ran only once or twice a week. I knew I had to get a move on. I also knew that trying to catch a train from here would be impossible, but even so I still went down to the station for a look.

Bulawayo is nicknamed the “City of Kings” but it is also known as “kontuthu ziyathunqa“, a Ndebele phrase for “smoke arising”. Apparently the name was inspired by the large cooling towers of the coal-powered electricity generating plant situated directly opposite the station. The plant is dormant now and the smoke has gone.

Sadly, there was no smoke or even diesel fumes arising at the station either. The attractive building was totally abandoned and empty. Although there are a few freight trains, Zimbabwe’s passenger services have been suspended since the pandemic and in 2025 showed no sign of ever being restored.

I walked into the station foyer. Frustratingly, they still had the schedule posted on a board that stood just in front of the locked platform gates. Services to Harare had only run three times a week but the sleeper to Victoria Falls was shown as departing here every night at 19:30.

Peering through the gates, I wondered if the dilapidated train stabled in one of the platforms was the one they used to use on the “Cape to Cairo” line to Victoria Falls. I could have jumped on here and woken up to the sights of Hwange National Park before arriving just in time for breakfast.

Cape to Cairo Highway

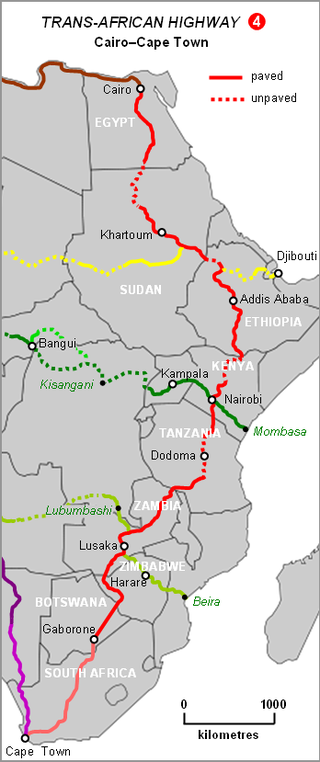

Still, if the Cape to Cairo railway line was not immediately an option, at least I would have a chance to travel along the Cape to Cairo Highway (Trans-African Highway 4) which also passes through Bulawayo. In fact, it runs broadly parallel to the railway all the way from Cape Town to Kapiri Mposhi and thereafter tracks the Tazara Railway well into the centre of Tanzania before finally turning north towards Dodoma.

The concept of the Trans-African highway system dates from the 1980s but the idea of a Cape to Cairo Road goes further back. In most of Zambia the route is known as the Great North Road, although the section that goes through central Lusaka is actually called Cairo Road. The bit that I would follow from Bulawayo to Victoria Falls is simply known as the A8.

So, now I had a route, all I needed was a bus.