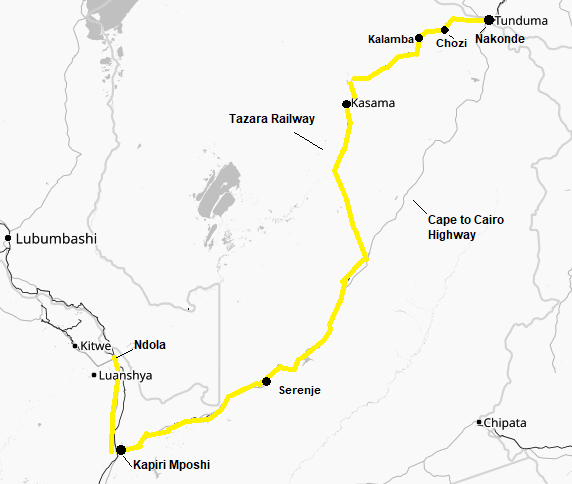

Using the Tazara Railway to get to the Tanzanian border

My journey

Having arrived in Ndola, I now planned to purchase my ticket on the Tazara Railway at the company’s local office. Then, after staying in Ndola for a few days, I would travel 200 km back to Kapiri and board the “Mukuba Express” to Nakonde on the Zambian/Tanzanian border. That train was scheduled to leave at 12:00 (noon) and arrive at Nakonde (around 900 km away) at 15:00 the following afternoon. I would then need to make my own way across the border into Tanzania and find a way of reaching Dar es Salaam.

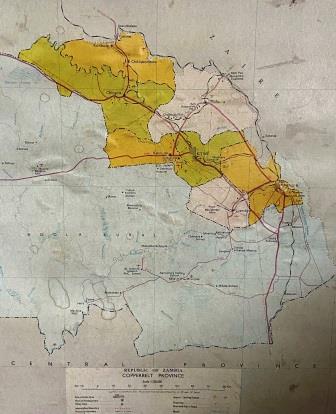

Copper

The next morning, I woke to find I could not open my left eyelid. The eye itself seemed quite infected, so I decided to go to a pharmacist. I found one close to the Tazara office in the centre of Ndola and managed to get eye drops and a lot of friendly reassurance. The Tazara office was not open until later, so I took myself off to the Copperbelt Museum just across the road.

There was a map on a wall in the museum that showed the extent of the Copperbelt in yellow. One of the stewards explained that prospectors used the presence of the “copper flower” (Becium homblei) on the surface as an indicator of where the copper might be found. Large scale extraction started in the early 20th century and the mineral is still Zambia’s largest export. The local word for copper is “mukuba”. The Tazara train I would be taking from Kapiri is named after it.

But the museum was not all about copper, in fact very little of it was. It was more of a general museum on life in the Copperbelt, with a mixture of exhibits that included stuffed animals, musical instruments and a collection of toys made from wire. The most interesting section dealt with local ceremonies and included a fascinating explanation of witchdoctors.

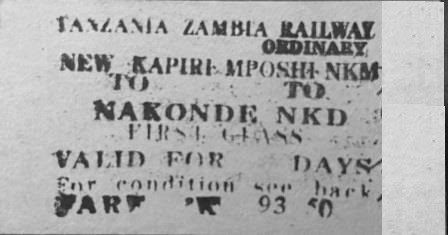

Tickets to Ride

You could not really miss the Tazara office, there was a large vinyl of a locomotive plastered across its windows. Inside were photographs of African and Chinese politicians posing in tunnels during the construction of the line back in the 1970s. The railway was built, with a lot of Chinese help, to enable Zambia to export its copper without having to transport it through the white-supremacist regimes of Rhodesia and South Africa. It opened in 1976.

I was dealt with quickly and efficiently. I paid 380 Kwacha (£10) and received a first class sleeper ticket on the “Mukuba” to Nakonde. In normal times I would have been able to travel from Kapiri all the way to Dar, but trains had not been crossing the Tanzanian border for several months. Worse still, whilst the Zambians would take me to within 3km of the border, on the Tanzanian side trains were only operating to and from Mbeya, 100km away. The connections in the Dar direction were hopeless.

Slightly worried after my experience on the Zambezi, I enquired about the reliability of the Mukuba; I wanted to know if it usually arrived at 15:00. The answer was “mostly, yes, but sometimes it is 14, although sometimes 16”. My main concern was that the Tanzanian border closed at 18:00 and if I did not make it across by then, I would need to stay and extra night in Nakonde. There was nothing I could do though, so I went off to buy a bus ticket for Kapiri. On the advice of the people at Tazara, I booked a seat with Power Tools on its service departing at 07:30.

A Walk around

I spent the rest of the day looking around the city. Ndola (population 600,000) was Zambia’s third largest settlement, but it was definitely not a tourist destination. In fact, apart from the Copperbelt Museum itself, the other main attraction was the 1961 crash site of the plane carrying Dag Hammarskjöld, second secretary-general of the UN. It was a little way out of town, so I decided to leave it until next time.

Walking around the centre of Ndola did not really feel like walking around a major city. It was pleasant enough, very modern in parts and had a very up-to-date mall. Yet it seemed more like a service centre type of town, the sort of place you came in from the surrounding area to buy an industrial food mixer or some air conditioning equipment. On my walk I saw outlets selling both of these things, and there was also a street with lots of shops selling cement and paint.

There were wide streets, quite a bit of traffic but very few people walking about. It was said that Ndola was the friendliest city in Zambia, but it was difficult to get evidence of that. I had found the people on the Zambezi train extremely friendly, but here they seemed a bit more reserved, if anything.

At lunch time I found a little cafe. There were a couple of guys sat outside eating the daily special of steak and beans, it looked good so I went inside and ordered the same thing. I tried to engage the waitress in a bit of conversation but she seemed too busy. The food was excellent though.

I visited a couple of pubs, but apart from exchanging a few pleasantries nobody seemed to want to talk. At the second place I was joined at my table by two guys who appeared from the car lot next door, they greeted a third guy and proceeded to sell him a van. They never drank anything. When they were handing over the keys, I asked for my commission and they smiled.

To Kapiri

The next morning, I was at the Power Tools bus stop for 7:00. I asked if the 7:30 was on time and without answering they took my ticket and changed it to the 6:30, which they said was now due at 7:20. The bus eventually turned up and was completely full when it left at 7:30.

The road south was in rather good condition and it was about to get better because they were busy building a second carriageway the whole way. In contrast to my seven hour jaunt on the Zambezi, the bus ride back to Kapiri Mposhi took less than two hours. If only they invested in the railways like this too.

New Kapiri Mposhi

It seemed that most of my fellow passengers were continuing on to Lusaka; I was one of only two people to get off at Kapiri. Even before I stepped off the vehicle I found myself surrounded by a group of taxi drivers all shouting “Tazara” at me. I smiled apologetically and said “Choppies”, pointing to the large supermarket I could see across the main road.

Choppies, part of a chain based in Botswana, turned out to be a good call. I got supplies for a late breakfast and enough food and drink to survive the next twenty four hours or more on the train. When I came out I noticed a guy sitting in a battered old Toyota. We made what I thought was quite a reasonable deal and he agreed to drive me the 3km to “New Kapiri Mposhi,” terminus of the Tazara Railway.

The station building at New Kapiri Mposhi was a monument to 1970s Chinese communist architecture. It certainly felt like something you would be more likely to see in Shanghai than in the middle of the Zambian Copperbelt. It served a town with a population of around 80,000, although most of its passengers, like me, originated elsewhere and just changed here.

Even though there was only sixty minutes to go before the noon departure time the place seemed almost deserted. I counted less than twenty passengers waiting. I wondered how the truncation of the line at the border was affecting revenue. Certainly, there were no international visitors around.

I went to the booking office, which opened an hour before the train was due to depart. I wanted to double check that my ticket was in order. I was told that everything was fine and that I should go to the first class lounge to wait.

I found the lounge the other side of a ticket barrier manned by four Zambian policemen. It was a long narrow room filled with about ten armchairs, there were portraits of the presidents of Zambia and Tanzania and a banner advertising the Tazara at one end, but little else. I sat there on my own. The armchairs were certainly better than the hard seats outside, but the big advantage was the plug socket to charge my phone.

Boarding the Train

I had been watching out of the corner of my (good) eye as the locomotive had collected the rake of coaches from a siding. Now it gently backed them into the platform. With around half an hour to go before departure we were allowed to board.

I walked up and down the platform before going to my own carriage. There were three baggage vans at the front behind the locomotive, then several third class seating coaches, a single second class seater, two catering vehicles and then a couple of second class (6 berth) sleepers and a couple of first class (4 berth) sleepers at the back. I was in the second to the last coach.

Inside, the Mukuba was a massive step up from the Zambezi, there were sheets and blankets on the beds, although no pillows. There was running water in the Asian style toilets, as well as dedicated wash basins half way along the carriage.

The compartment was designed for four occupants and at first I thought I might be lucky enough to get it all to myself. Then, just before the train started moving, another guy joined me. He announced he was going as far as Kasama; he lived in Lusaka and was travelling to visit family for a few days.

We set off at dead on 12:00. Immediately I noticed that we were moving a bit faster than on the Zambezi. As we passed through now familiar scenery, lots of cornfields and lots of sunflowers, I calculated that we must be reaching at least 40 km/h or even more.

Unlike the Zambezi though, the air conditioning did not seem to be working, so we agreed to open the window. It was also obvious that the compartment had once enjoyed double glazing, but the outer pane had been smashed away and not replaced.

I asked my roommate when he expected to arrive in Kasama (about two thirds of the way to Nakonde) but he admitted to having no clue. Then he jumped up onto the top bunk opposite me and promptly fell asleep. I went off to find the buffet car.

The Train

The train set that we were travelling on was the more modern of the two in use on the Tazara. It had been delivered in 2016 and, allocated to the Zambians, it normally made a weekly round trip from Kapiri to Dar. Designated as “express,” it stopped only at the main stations and used the service title “Mukuba”. Its older Tanzanian counterpart made a similar round trip but was designated “ordinary” and stopped at all of the stations, took a little longer and used the title, “Kilimanjaro”.

With the Tazara service effectively severed at the moment, both trains were now confined to making two weekly round trips on their own sides of the border. The Mukuba was heading back and forth between Kapiri and Nakonde, whilst the Kilimanjaro was shuttling between Mbeya and Dar, leaving a 100 km gap in the middle.

The train was a little worse for wear in places but overall, it was very pleasant, especially if you had a thing about turquoise. Just so that nobody would be in any doubt as to where the train had come from, there were China Aid stickers everywhere.

There were two catering vehicles. The bar lounge car was divided into three sections, a part with longitudinal seating, another bit with seats with tables and a serving area. The restaurant car had tables in one half and a kitchen in the other.

When I got to the bar lounge car it seemed there was already a bit of a party going on. It was less than an hour into the journey. I got myself a beer and a window seat and joined in. It was a great crowd, some guys on their own and some couples, mostly people from Lusaka heading to see relatives along the line.

For the next few hours we chatted, listened to music and even danced. Someone was playing songs by South African reggae artist Lucky Dube (1964-2007) and they seemed to suit the rhythm of the moving train perfectly.

Amongst all the revelry I noticed an older guy sitting by himself at the rear of the carriage and smiling at everyone. I went and sat with him and we had a quiet beer together.

An evening on board

Around 16:00 I returned to my compartment for a bit of a rest. The other guy was still sleeping in the top bunk. I looked at our position on MAPS.ME and it seemed to me that the train was making excellent progress. I started to wonder if we could actually arrive at Nakonde early.

I had dinner in the restaurant car around 19:00. There was a choice of fish with nshima or chicken with nshima. I chose the chicken and it was rather good. After I had finished I went back to the bar car and I chatted with an ex-policemen for a bit. There was a drunkard trying to cause a bit of trouble but, worse still, people were hitting him to try and get him to stop. I decided to call it a night and wandered back to my compartment.

I dozed off around 21:00, then sensing the train had stopped and hearing a lot of people in the corridor I woke up. It was midnight. The door opened and standing there was a young boy, probably about ten years old. When I asked him what he was doing, he explained his mother worked for Tazara and she had told him to sleep in our compartment until she found somewhere else for him. “Fair enough” shouted my roommate from his top bunk. “Fair enough”, I found myself agreeing. The boy headed to the opposite bunk and I fell back asleep.

I was woken again at around 5:00 by the noise of my roommate leaving the compartment. We had reached Kasama. The little boy was still sleeping on the lower bunk opposite mine, but as we departed Kasama, his mother came along to collect him. I would now be alone in the compartment for the rest of the trip.

An elongated stop

Around 07:00, just before the train pulled into Kalamba, I went to the dining car for breakfast. They were serving bread and omelette with tea, but sadly no coffee. I was sat opposite a woman and we got talking.

She told me her husband had died three years before. She had then set up a business buying vegetables and other goods in Nakonde and Tunduma and then taking them back to Serenje where they could be sold for a higher price.

The difference in value more than paid for the train fare, she claimed. She was not the only one doing this either, she explained, there were a lot of people on the train doing the same thing. It seemed slightly odd, but it I supposed it provided the Tazara with passengers.

The train was now making incredible progress. By 08:45 we had reached Chozi, in theory just an hour and a half short of Nakonde. We had also caught up with the Rovos Rail train we had been following on the Zambezi more than four nights before. The luxury train was stabled in the platform next to us and I guessed it might have spent the night there.

I got out and wandered around the station. Some of the people on the Rovos train were peering through the windows of their en-suite cabins. The train had obviously started in South Africa and was heading for Dar on a slower schedule than us. It occurred to me that it had followed the Cape to Cairo Railway from Bulawayo and it was currently the only way of travelling on that line.

The carriages were beautifully polished and the two locomotives (we only had one) had their own dedicated oil tanker wagon. It was certainly a wonderful way to travel. I knew it came with a wonderful price tag too and perhaps it did not provide quite the same opportunity to meet the locals as the Zambezi and the Mukuba did.

In the end we stayed at Chozi for almost two hours, during which time the locomotive was changed. We departed at 10:30, leaving the Rovos train behind and set off for what I thought could still be an early arrival at Nakonde.

A climb to the finish

I went back to the dining car for a tea and got chatting to a Tazara official. He was Zambian but was heading to the head office in Dar where he worked. He was the first person on the train that I had met who was actually heading further into Tanzania than Tunduma.

We had a long chat about the problems of the Tazara, the lack of investment and the various infrastructure failures. There was a vicious circle; lack of money for maintenance affected reliability and that then drove freight clients away and reduced revenue further. Apparently the latest problem, the ceasing of cross border passenger working, was down to credit issues that prevented the two countries pooling fuel, or something like that.

More positively, we talked about recently announced plans for more investment and the hopes of creating more traffic and one day even running all the way to Lusaka. Then, I mentioned the fact the Mukuba was early and raised the possibility of making a connection with the Kilimanjaro from Mbeya. “Mr Tazara” suggested it was possible but that I should not get my hopes up.

I did some calculations; in order to get to Mbeya for the train to Dar, which left at 17:00 Tanzanian time (one hour ahead of Zambia), I would need to be across the border and catching a bus, if there was one, by around 15:00. Allowing an hour for the border, maybe, that meant an arrival into Nakonde of no later than 13:00 Zambian time. It looked doable.

In the end though, “Mr Tazara” was proved correct. The train seemed to be in no hurry to get to the terminus. In fact, as we approached the hilliest and most difficult part of the line in Zambia, it slowed right down and made a few longish stops at smaller stations. The locomotive was struggling as we negotiated the reverse curves on the last leg.

The beautiful scenery we were now passing through ushered me to a decision. The bit I would miss between Nakonde and Mbeya was actually the most scenic part of the line, so better to come back another day and do it then. Better to do that than embark on a mad frantic mission to catch the train from Mbeya that I could very well end up missing. By the time we arrived at Nakonde and I had alighted it was 13:20, and I had already resolved to get the bus.

After a spot immigration check on the way out of the station, I found a group of motorcyclists waiting to ferry passengers to the border. I settled on a price of 60 Kwacha (2 USD) with one of them and set off hanging on for dear life on the back of a bike with no crash helmet. The driver was extremely skilled and negotiated the dirt tracks that led from the station to the frontier with aplomb.

Within fifteen minutes I was in the “one stop border” immigration building and, finding no queue, had already presented my passport to the Zambian official and received an exit stamp. There was a queue at the adjacent desk to enter Tanzania though, and it was actually quite a long one.