July 1958- April 1959 “Planning for Construction”

Planning the route of the new line began immediately. Responsibility for the massive civil engineering project fell to Shigenari Oishi. (Oishi, along with Shima and his successor Matsutaro Fujii, was eventually awarded the prestigious Sperry Award for transport engineering in 1966). Although aircraft were used in surveying the route, Oishi also walked the whole distance himself.

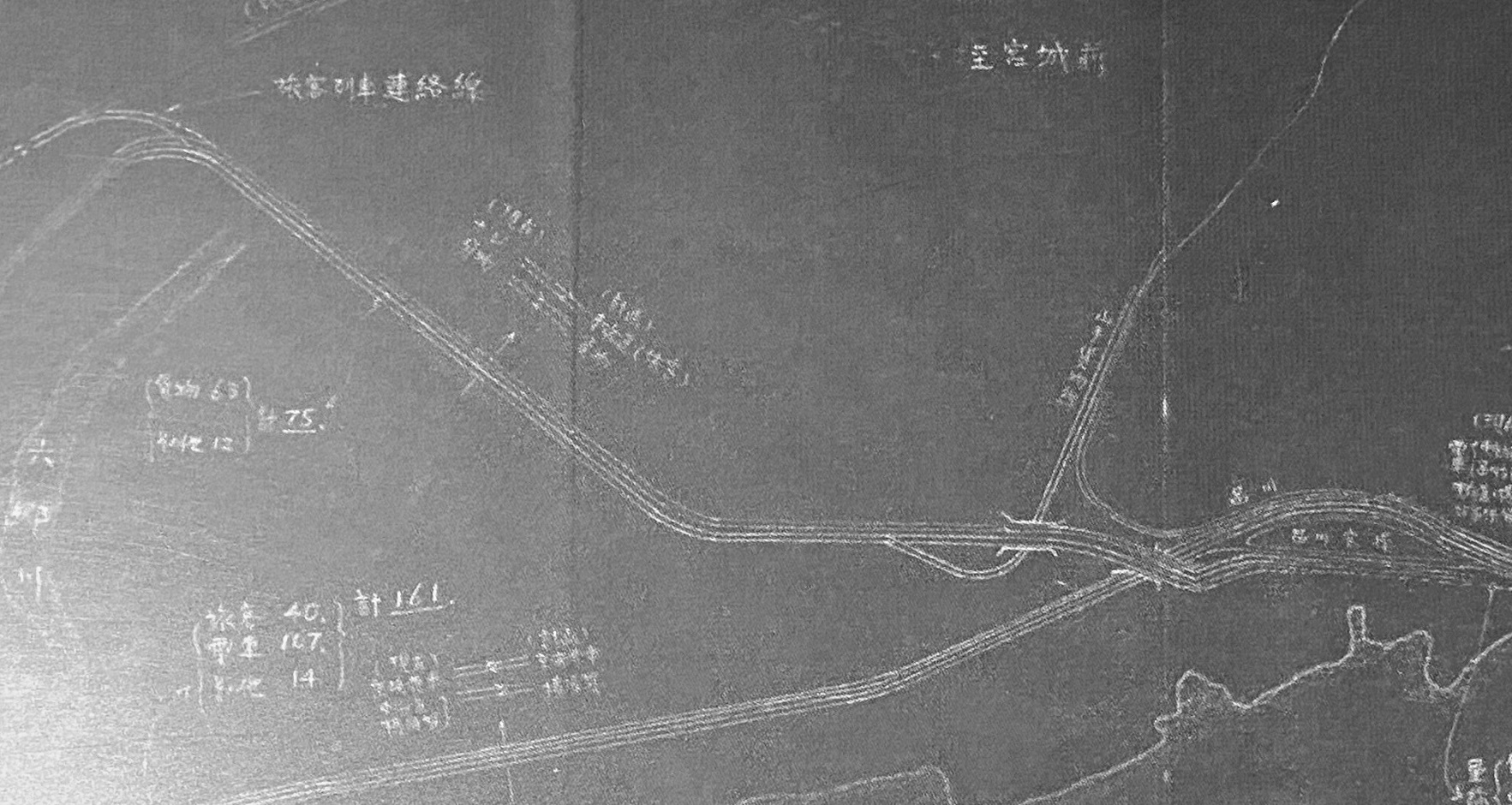

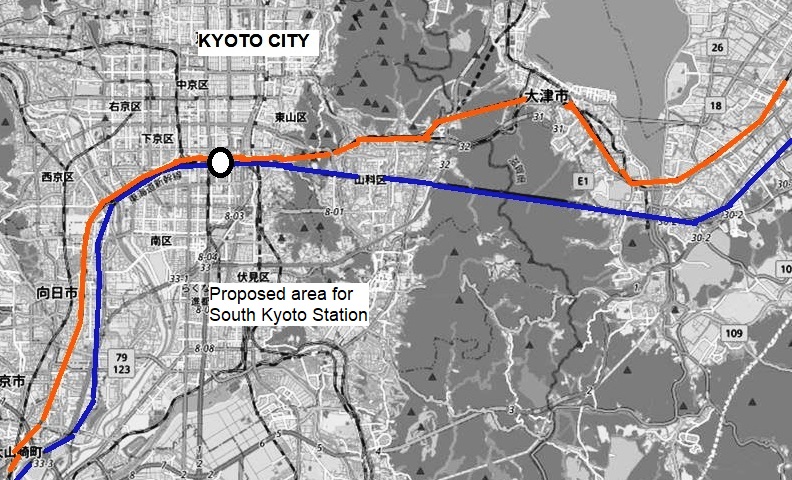

It was decided that a substantial part of the planned 1940 route would be used, not least because land purchased back then (marked in yellow below) was still held by JNR. The initial plan, as in 1940, was for a direct route from Nagoya to Kyoto (shown in red below) avoiding Sekigahara and its snow-related problems. A new 12km tunnel through the Suzuka Mountains was envisaged, helping to shorten the distance from Tokyo to Osaka to 500km.

After geological surveys were conducted in the Suzuka area it was found that tunnelling would be difficult, costly and time consuming. The decision was made in April 1959 to route the line via Sekigahara and Maibara adding around 15km to the total distance. This meant that the line could be open in time for the Tokyo Olympics in October 1964. The games were actually only awarded to the city in May 1959, but their opening date quickly became a deadline for completion. Unfortunately, the decision also meant that snow-related delays would plague the line from its opening. They continue to this day.

The new 515km line would run close to the Tokaido Line for much of its length although its use of straighter alignments made it 40km shorter overall. Eight of the ten intermediate stations on the Shinkansen route were eventually built alongside the old Tokaido Line ones. However, existing stations at Yokohama and Gifu were bypassed and stops in nearby (what were then) rural locations at Shin-Yokohama and at Gifu Hashima were provided as compensation.

Four construction bureaus were created to manage the mammoth project. Building the first 3km out of Tokyo was thought to be an especially difficult task and it was hived off to a separate Tokyo Bureau. The Tokyo Main Line Bureau would then build the line to the 84km point just past Odawara. This section would include a 30km test track to be built on already acquired land and scheduled to open much earlier.

The Shizuoka Bureau would continue the line to the 261km point between Hamamatsu and Toyohashi on the border with Aichi prefecture, the Nagoya Bureau would then be in charge to the 391km point just east of Maibara and the Osaka Bureau would complete the line through Kyoto and into Shin Osaka. Eventually each bureau would control the different construction sites in its section. Shizuoka, for example, would oversee more than 30 locations based around the various tunnels, stations and bridges.

The most immediate task for each bureau was to fix the final details of the undefined part of the route and acquire the land to build on. 420km of the route still needed to be purchased and in order to complete this task JNR hired in 200 experts in land acquisition. Negotiations were needed with the representatives of more than 100 cities, towns and villages and with around 50,000 individuals; a fair amount of opposition was encountered along the way.

April 20 1959, “Construction Begins”

Meanwhile, along the 100km of route where land was already owned, construction could begin. Formal ministerial authorisation was given on April 13, 1959 and a week later, on April 20, 1959, a ceremony was held at the eastern portal of the part-completed Shin Tanna Tunnel to mark the beginning of construction. Around 80 people were in attendance including a Shinto priest. Sogo wielded the first shovel so hard he actually broke it in the process.

The whole line would eventually boast 66 tunnels with an aggregate length of 68.6km or 13% of the total 515km. The time taken for their construction would be the biggest determining factor in how long the project would take to complete. Constructing tunnels presented its own problems, with a constant battle against water ingress being fought in several bores including Shin Tanna itself.

With an aggregate length of 57.1km (11% of the total line), the bridges that were needed to span the many wide estuaries along the Tokaido route were another engineering challenge. A common cantilever design was adopted to simplify things and speed progress.

The line also involved the construction of long sections of viaducts especially where the railway would be carried through urban areas high above roads to avoid the need for level crossings. At 115km the total length of viaducts represented around 22% of the route, although unprecedented at the time, this figure was low compared to later Shinkansen projects which featured viaduct for almost all sections not in tunnel.

By comparison with later projects, the amount of conventional soil road bed on the Tokaido Shinkansen was very high at 274km (53%) with cuttings accounting for around 44km (8%) and embankments 229km (44.6%).

Construction was particularly difficult where the railway had to be threaded through existing built up areas. Building the new line above existing freight tracks on the approach to Tokyo proved very tricky.

May 1960 / May 1961 – “Funding from the World Bank”

In 1958 the initial estimate of the cost of building the new railway had been 172.5 Billion Yen. Sogo planned for JNR to borrow the money for construction, so with interest also considered an eventual total outlay of 194.8 Billion Yen was foreseen. Whilst it was envisaged that all the money could be sourced domestically, Sogo was persuaded to borrow from the World Bank, allegedly to make it more difficult for the Japanese Government to cancel the project.

In May 1960 representatives of the World Bank came to Japan to investigate the project and a year later, in May 1961, executives of JNR visited Washington to sign an agreement for a loan of $80 million, equivalent to around 28 Billion Yen or about 15% of the then estimated total cost. The loan was eventually paid back in 1981

In the end, costs were revised upwards several times and ended up at 379 Billion Yen, almost double the original figure. There were various allegations against Sogo. It was said that he had purposely underestimated in the first place to get the project accepted and that he had been diverting resources from elsewhere in JNR to make up the shortfall. In 1963 he resigned as JNR president; Hideo Shima went with him. Ironically, neither man was invited to the opening ceremony in 1964. Sogo is now commemorated by a memorial on platform 19 at Tokyo Station.

October 1961 – Whole Route Fixed

Although construction was progressing along most of the line, it was not until October 1961 that the final details of the route were fixed. Land purchase proved more difficult than anticipated and in several areas the Land Expropriation Act had to be resorted to. There were issues along the whole line and in some areas, such as the route just south of Shinagawa and through Hamamatsu, the workarounds resulted in sharper than planned curves which still constrain speed to this day.

Nevertheless, the biggest problems were encountered west of Nagoya where no land had been purchased for the 1940 project. Although Nagoya was positive and aided land purchases for the near 20km elevated section through its city, the exact routing northwards avoiding Gifu and the siting of the station at Gifu Hashima was subject to much political wrangling and took time.

At Kyoto, one idea had been to route through the south of the city to a new station, in order to provide a straighter alignment. The overall plan called for the fastest trains to stop only in Nagoya and pass through Kyoto to reach Osaka in 3 hours. The Kyoto city government lobbied hard for the new railway to serve the existing station and for all trains to stop there. It promised to help with land acquisition along the route. In the end, the city got its way on the route but securing the land proved especially problematic and was not totally completed until October 1963. The debate on whether Kyoto would be a stop for the fastest trains continued.

Meanwhile at Osaka it had been decided that, rather than terminate at the existing station in the city centre, the new line would be kept on an alignment that would facilitate westward extension to Okayama and beyond (as happened in 1972). After some difficulty securing land, the site for a new interchange was finalised in January 1960 with construction starting in February 1961. The station, named Shin-Osaka, was created at a point where the new railway crossed the Tokaido Line at right angles. A set of platforms were provided on the old line linked by escalators to the new Shinkansen station above it.

June 23, 1962 – First 12km of the “Model” Test Track Completed.

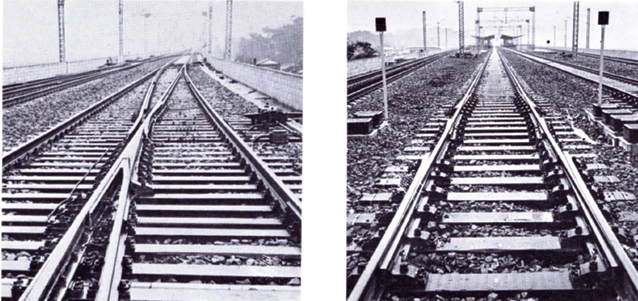

Back in 1958, under the leadership of Hideo Shima, JNR had established a set of Shinkansen standards which governed track-bed width, rolling stock and electrification systems. Starting with the basic decision to use standard gauge, the standards defined a maximum curve radius of 1800mm, and a maximum incline of 15%. Continuous welded rails and pre-stressed concrete sleepers would be used for the track. High speed points would also be employed.

The maximum intended line speed would be 210km/h but the line would be designed, with a safety factor included, for operation at 250km/h. The standards prescribed overhead electrification at 25kv AC at 60HZ frequency. Automatic transformer stations would be used, and the catenary would be constructed in such a way as to have the contact wire at an almost constant height above the track for the whole distance, to enable smaller pantographs to be used.

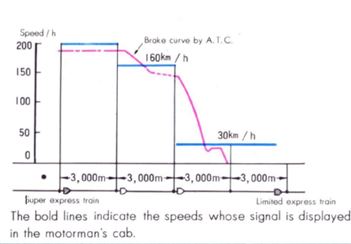

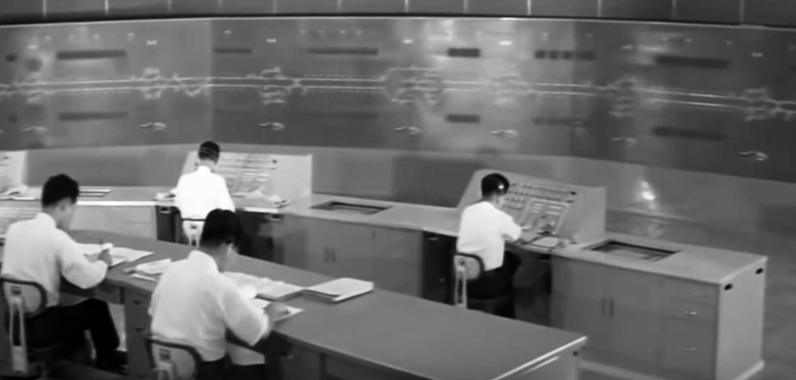

Meanwhile, instead of conventional lineside signals, the line would be equipped with Automatic Train Control (ATC), an innovative track transponder system designed to automatically decelerate the train according to occupancy of the line ahead. ATC would work in tandem with the Central Train Control (CTC) system which would allow the control centre in Tokyo to remain in contact with trains even when they were in tunnels. it was connected to a system of wind sensors:, earthquake monitors and emergency stop buttons to ensure maximum safety.

Many of these prescribed systems were new and untried, so in order to test as much as possible before equipping the whole line, a 30km test track, known as the ” model line”, was constructed between Odawara and Shin Yokohama. It would be later incorporated into the finished line. It was built in stages from Kanonomiya, over the Sakawa River from Odawara, with the first 12km opening in June 1962. In October it was extended east to Ayase giving 37km of testing line.

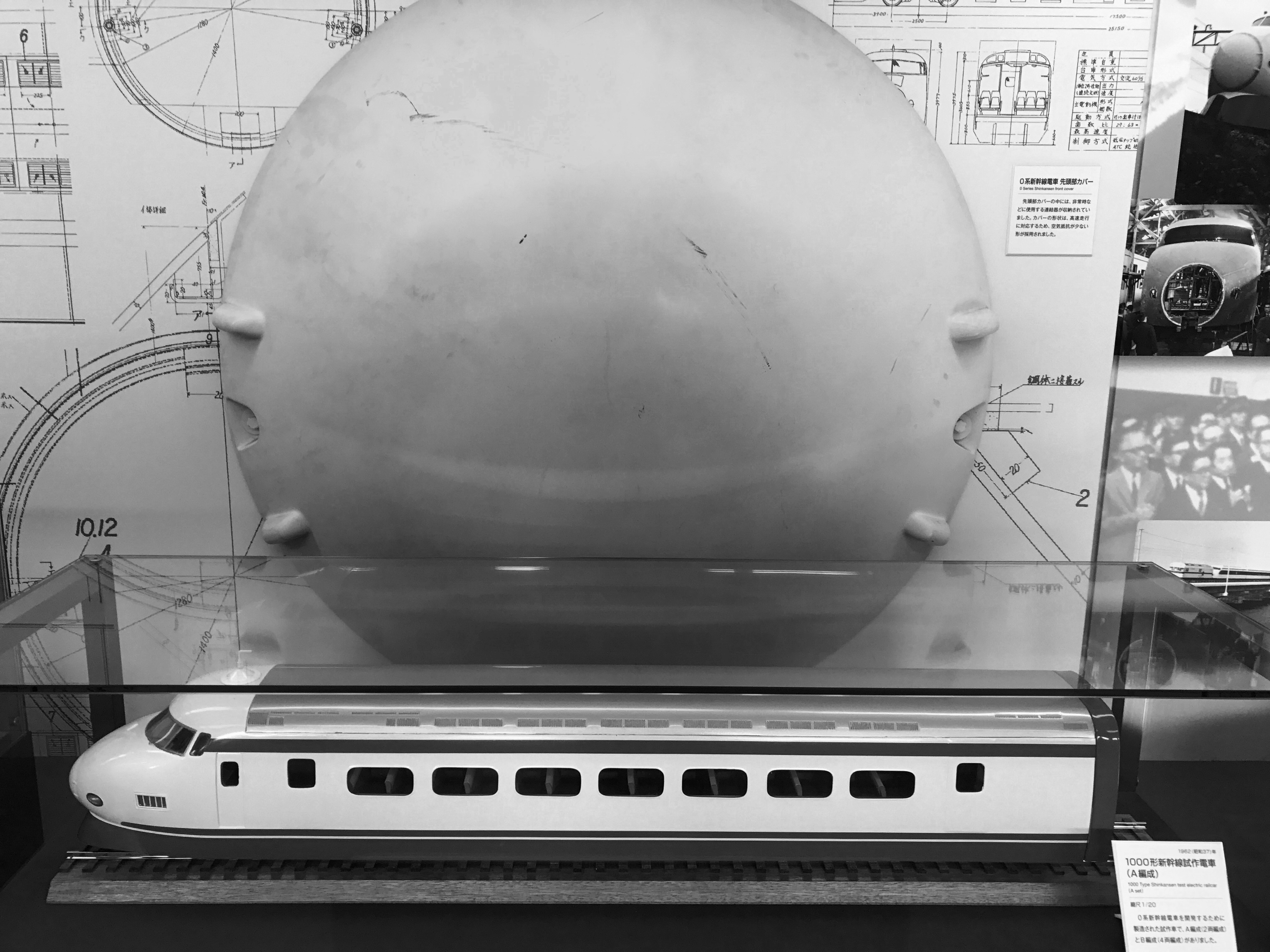

The model line included several tunnels and the Sagami River Bridge; it was constructed and equipped to exactly the same standard as that planned for the rest of the line, including full electrification and ATC systems. A test facility was established at the Kamomyama end with car sheds to house two prototype trains which were delivered soon after opening.

The trains consisted of one two car “A” set and one four car “B” set. In outward appearance both trains resembled the production Shinkansen trains which would follow. A series of tests using both were made to determine not only the final train design but also the performance of the railway and the ATC systems. Among the topics studied were current collection, bogie design, brake adhesion, trackside wind, ground vibration and the effects of trains passing each other at speed and in tunnels.

The testing reached its zenith on March 30, 1963 when the B set established a new Japanese rail speed record* of 256km/h. The decision to create the model line was vindicated by the wealth of experience gained and the lessons learned. The two trains ran a total of 250,000km on both lines over the course of two years. The test centre closed in April 1964 just as the model line was being linked to the rest of the system.

*The French still held the world record of 331km/h set in 1955

August 19, 1963 – Design of Production Trains Fixed

In conjunction with the work on the model line and other testing elsewhere, the design of the production trains was slowly determined. Production of the initial batch of 30 12-car trains was contracted out to several manufacturers with final assembly being carried out at JNR’s Hamamatsu works, located almost at the centre point of the new line. The works would carry out all major overhaul of the trains, a role it still performs today.

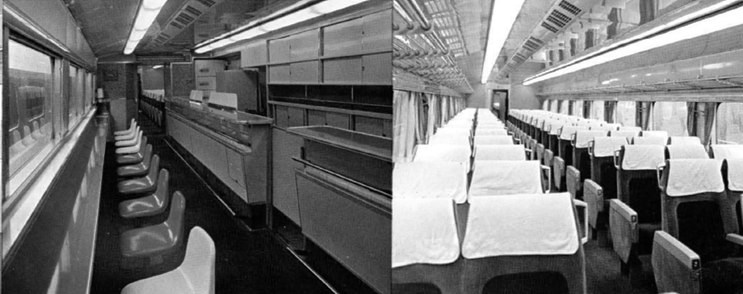

Each 12 car train had 10 standard class and 2 first class coaches. 2 of the standard class coaches included buffet counters. The trains were equipped with air conditioning, pressurisation systems and toilet retention tanks. The cars rode on the latest version of the high-speed bogie developed by the RTRI.

Each vehicle was equipped with its own motored axles, with DC motors being chosen after experiments were conducted using AC motors as an alternative. Every second vehicle had a pantograph, the relatively small design being possible because of the constant height of the trolley wire on the railway. The trains were also equipped with regenerative braking systems in addition to disc brakes and featured a protective guard underneath the skirt at the front.

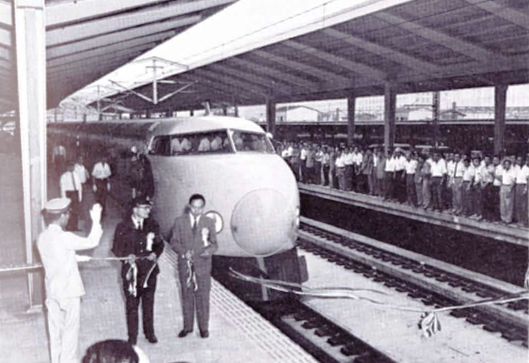

The first pre-production unit was delivered in February 1964. Meanwhile in April 1964 the two main depots at either end of the line, Shinagawa in Tokyo and Torikai in Osaka, were opened and made ready to receive the production trains. At the end of July, one of the brand new trains was exhibited to the public at Tokyo Station.

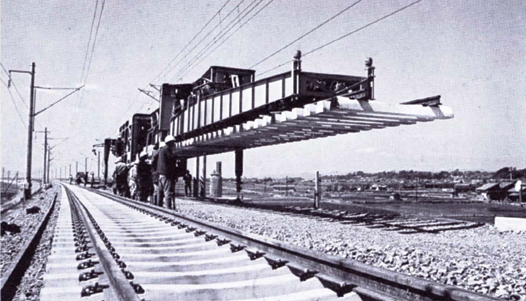

July 1, 1964 – “Track completed”

By early 1964 tracklaying on the line was almost complete. A section from the model line south to Atami was opened in the first few months of the year and then on April 28th a stretch of more than 100km between the depot at Torikai (Osaka) and Maibara became available for the engineers to conduct longer distance train testing.

Over 30,000 test riders experienced the new line between May and September. Testing at the maximum intended speed of 210km/h began between Shin-Osaka and Maibara from June 30th. The very last rail on the whole line was laid in a ceremony in the Kawasaki area, just south of Tokyo, on July 1st 1964.

Also nearing completion were the stations along the line. Their design embodied the “Standard, Simple and Smart” ethos that was being applied to the whole railway. Their platform sheds, ticket counters, passenger displays and even their seats followed common designs. Whilst the large terminals such as Tokyo and Shin Osaka were bigger and incorporated shopping arcades underneath them, the majority of stations looked quite austere with little in the way of platform canopies and certainly none of the sales kiosks and other furniture that would be added in subsequent years.

July 8 1964 – “Train Names Decided”

A competition had been held to decide the nickname of the line’s super express train and over 500,000 entries had been received. The winner was “Hikari” (Light) It was then decided to name the limited express (all stations) service “Kodama” (Echo) given the connection between the speed of light and the speed of sound. The choice also made sense as the existing “Kodama” services on the Tokaido Line were destined to be discontinued, in common with most of the other daytime express services, and the trains that had formed them transferred elsewhere.

July 25th 1964 “First full line test run”

With the line finally completed, the first test run took place on July 25th 1964. A full-size 12-car production train made the very first journey from Tokyo to Osaka travelling at just 30km/h for the whole distance. The event was filmed and some of it relayed live on NHK, Japanese television. At many bridges along the route well-wishers gathered to watch the first train pass.

It was already dark by the time the train pulled up at Torikai depot just short of Shin-Osaka. The waiting photographers and camera crews were there to record not just a key moment in rail history but an event of national significance.

Throughout August testing at gradually higher speeds continued and on the 15th, the first trials with the ATC fully activated took place. Towards the end of August, the first full practice runs of the 5-hour “Kodama express” all stations schedule and the 4-hour “Hikari super express” schedule were also successfully conducted.

August 19, 1964 – “Schedule and Fares”

With little more than a month to go before opening, it was finally announced that the Hikari super express trains would stop at Kyoto as well as at Nagoya. After the track bed had had time to settle (from November 1965 as it happened) their end-to-end transit time would be cut to 3 hours 10 mins. The 10 minute penalty on the original target 3 hour time perhaps a result of the extra stop and the diversion into Kyoto Station.

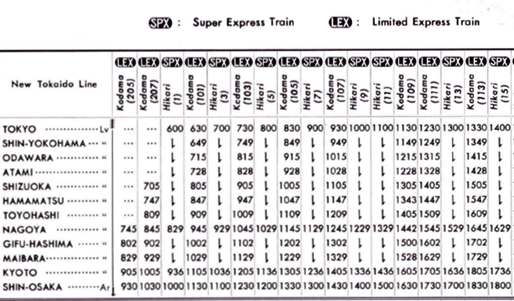

It was revealed that in the initial schedule to be used from October 1st, there would be Hikari trains departing Tokyo for Shin-Osaka every hour from 6:00 until 20:00 with just one gap at noon. Kodama trains would also run hourly between 6:30 and 18:30 with a gap at 10:30. There would also be short Kodama runs from Shizuoka and Nagoya to Shin Osaka in the morning and in the evening, at 20:30 and 21:30, from Tokyo to Nagoya and Shizuoka. A similar schedule would operate in the opposite direction.

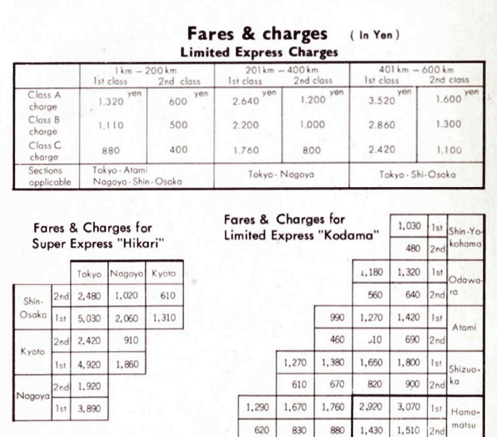

An “ABC” fare structure was also announced. A supplementary fare would be payable according to the speed of the train. For the initial Kodama 5-hour service only the cheapest “C” fare would apply. The 4-hour fare was designated “B”, and the most expensive “A” fare would be introduced only when the Hikari trains were speeded up to 3 hours and 10 minutes. The same basic system was also applied to first class fares. The ordinary fare was set around 3,000 Yen for the whole trip from Tokyo to Shin Osaka, then about 50% of the cost of flying. All trains were to be reservation-only at the start of service.

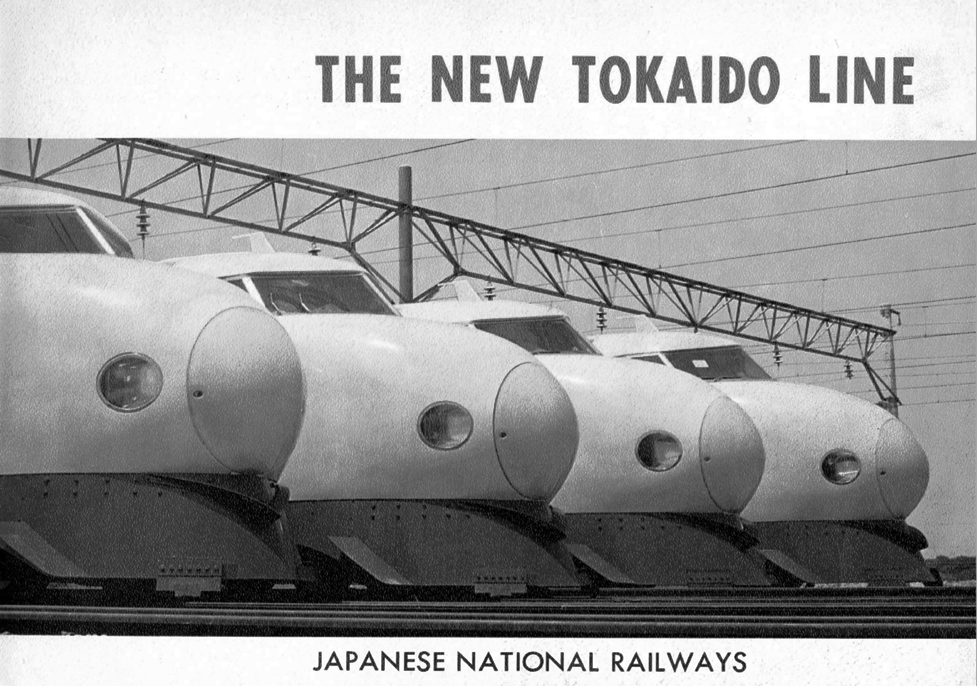

October 1964 – “The New Tokaido Line”

With the opening day approaching and the eyes of the world on Japan on the eve of the start of the Tokyo Olympics, the new railway was marketed to the world. The English title “New Tokaido Line” was used in all publicity and on signage at the stations.

The word “Shinkansen” did not appear at all in the glossy brochure produced to explain all the features of the new system and its trains to curious foreign visitors. The phrase “old Tokaido Line” which had no equivalence in Japanese was also used to describe the Tokaido Line. Even “Bullet Train” was limited to a sentence describing the 1940 system in the official publication, although it didn’t take the world long to adopt it as the unofficial name.

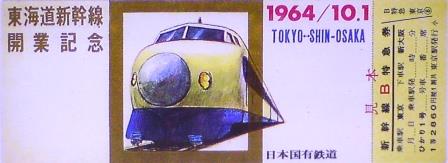

October 1st 1964 “Opening Day”

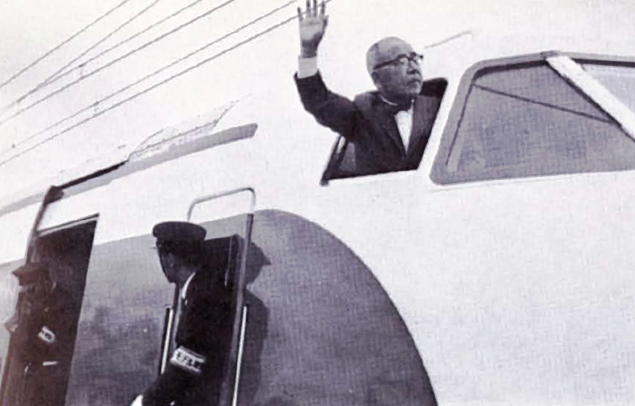

The line officially opened to traffic on Thursday October 1st 1964, nine days before the start of the Tokyo Olympics. Small ceremonies were held up and down the line, but most of the attention was on Tokyo where President Ishida, Sogo’s successor as head of JNR, cut the ribbon just before 6:00am and everyone watched as the first Hikari left for Shin-Osaka.

A more formal ceremony was held at the JNR Headquarters at 10am with the Japanese Emperor and Empress in attendance. A party was then organised the same afternoon at Tokyo’s Okura Hotel, and attended by more than 1000 guests including international dignitaries.

The Tokyo Station ceremony is captured in the last few minutes of JNR’s film Tokaido Shinkansen. One of the new trains is then shown speeding westwards. In the driver’s cab the speedometer gently rises to 210km/h, whilst inside the carriages the passengers look comfortable and contented. In the final moments of the film, the train speeds past the Meishin Expressway near Gifu-Hashima. There seems to be a symbolism here; the railway has taken on the car, and it has won.

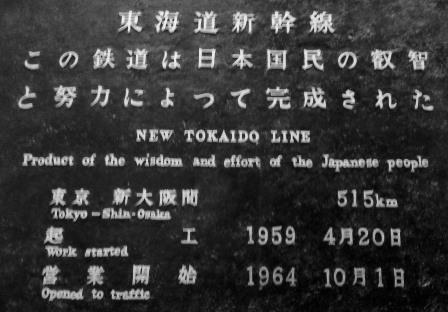

Still displayed at Tokyo Station and replicated at several museums in Japan, a plaque commemorates the opening day. The rather moving words suggest that the line was completed as a result of the effort and wisdom of the Japanese people. It is a nice touch and evidence that the Japanese often celebrate teamwork rather than individual achievement.

Nevertheless, it should also be acknowledged that the Tokaido Shinkansen would never have even been started without the contribution of extremely talented engineers like Shima, Oishi, Miki and Matsudaira, and of course without Sogo himself. Without them the development of high speed railways around the globe might have been very different. We still owe them a great debt.

Sources / Further Reading

The following are in my personal collection –

English language Books

-

- Iwasa, Katsuji and others (2015) Shinkansen -The Half Century – Kotsu Kyoryoku Kai Foundation

- Free, Dan (2008) Early Japanese Railways 1853-1914 – Tuttle

- Freeman Allen, G. (1978) The Fastest Trains in the World – Ian Allan

- New Tokaido Line (1964) – Japan National Railways

- Iwasa, Katsuji and others (2015) Shinkansen -The Half Century – Kotsu Kyoryoku Kai Foundation

English language Journals

-

- Intersect – October 1989 – “Happy Birthday Bullet Train”

- Modern Railways – 1964/1965 Various

Japanese Language Books (Titles translated)

-

- Suda, Hiroshi (2010) Tokaido Shinkansen II – JTB Publishing

- Miura Mikio / Akiyama Yoshihiro (2008) High Speed Trains of the World- Diamond Publishing

- Takahashi Dankichi (2000) The Men who built the Shinkansen –Shogakukan

Japanese Language Journals (Titles translated)

-

- Rail Magazine – 2008-8 “0″ Series Final Stage

- Tetsudo Journal – 2024-4 Tokaido Shinkansen 60 Years

- Railway Time Travel Series (2010) 1964 Railway Journey

- Shinkansen Explorer (2019- Spring)

- 200 Secrets of the Shinkansen -(2018) Mook Publishing

Website Links (Valid in 2024)

-

- The Tokyo to Osaka Line: A history #1 A really wonderful multi-part history of the Tokaido Shinkansen including many unique photographs

- Guardian Article on the 50th Anniversary

YouTube Links (Valid in 2024)

With Japanese commentary / No commentary