A lot has been written over the years about the late 19th Century plan for a railway linking Cape Town with Cairo. This is my own brief and modest account.

Cape to Cairo

The idea of a railway to link together the string of British colonies on the eastern side of Africa had first been mooted by the Daily Telegraph in the 1870s. Early plans actually called for a series of railway lines connecting into lake steamers to cover a whole distance of more than 6,000 miles (9,600 km).

Starting Out – Cape Colony

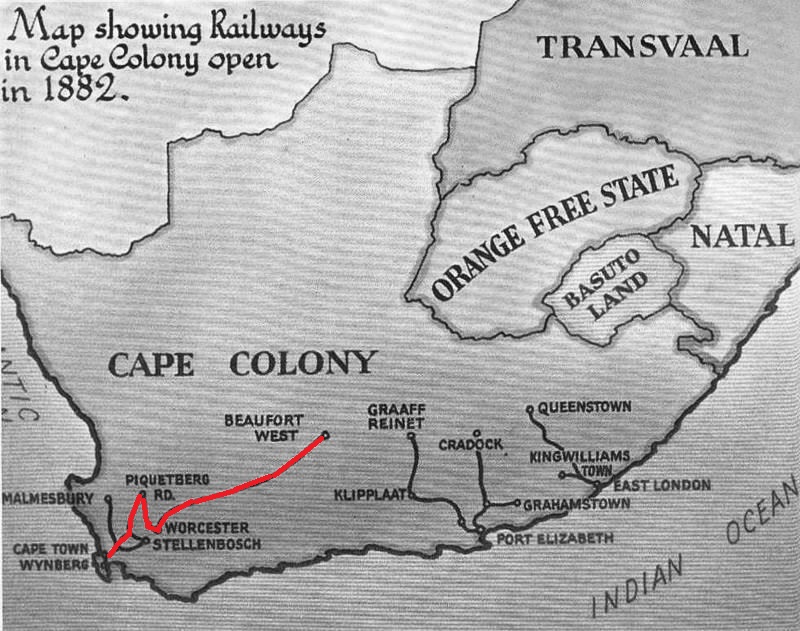

What would eventually become the first stage of the “Cape to Cairo” route was constructed entirely within the British-held Cape Colony. It was built by Cape Government Railways as part of a plan to connect Cape Town with the colony’s mineral-rich interior.

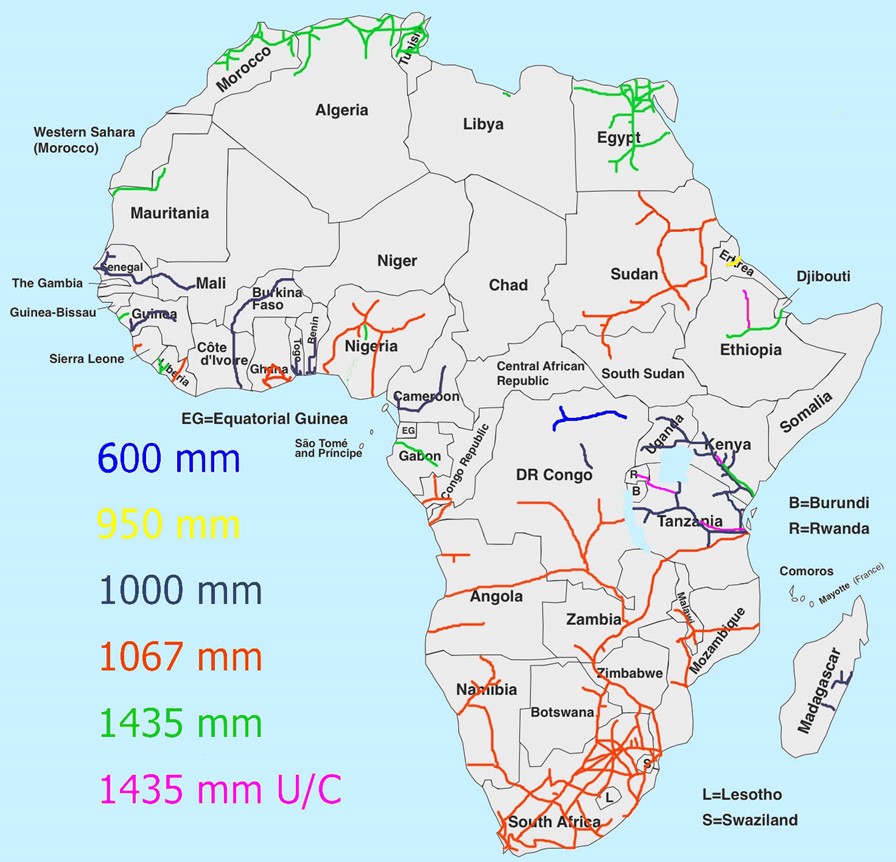

Faced with significant challenges in the mountains just north of Cape Town, the engineers abandoned plans to use Standard Gauge (4ft 8.5in / 1435mm) and chose 3ft 6in (1067mm) instead, thus giving rise to the term “Cape Gauge” still used today. The line opened to Beaufort West in 1880, and then, skirting along the border of the Boer-controlled Orange Free State, reached Kimberley in 1885. The town was already at the centre of the colony’s diamond mining industry and by the late 1880s it was dominated by Cecil Rhodes and the De Beers company.

Rhodes, having made his fortune from Kimberley’s diamond mines, began to champion the idea of “opening up” for mining and white settlement the land that lay to the north of the British protectorate of Bechuanaland (present-day Botswana). This area included Matabeleland and Mashonaland, populated by the Ndebele and Shona ethnic groups.

Fearing German, Portuguese or Boer interference, Rhodes moved to act quickly and in 1889 was instrumental in the formation, by royal charter, of the British South Africa Company (BSAC) which aimed to capitalise on the expected mineral wealth of the whole area which, although initially known as “Charter Land”, was destined to become Rhodesia.

After the failure of a negotiated solution, the armed forces of the BSAC defeated the Ndebele in the First Matabele War in 1893 and the company began to establish settlements in the area. The railway became an important instrument in carrying out its plans. It was the BSAC rather than the Cape Government Railway who oversaw construction of the line north from Kimberley, to reach Vryburg in 1890 and Mafeking in 1894.

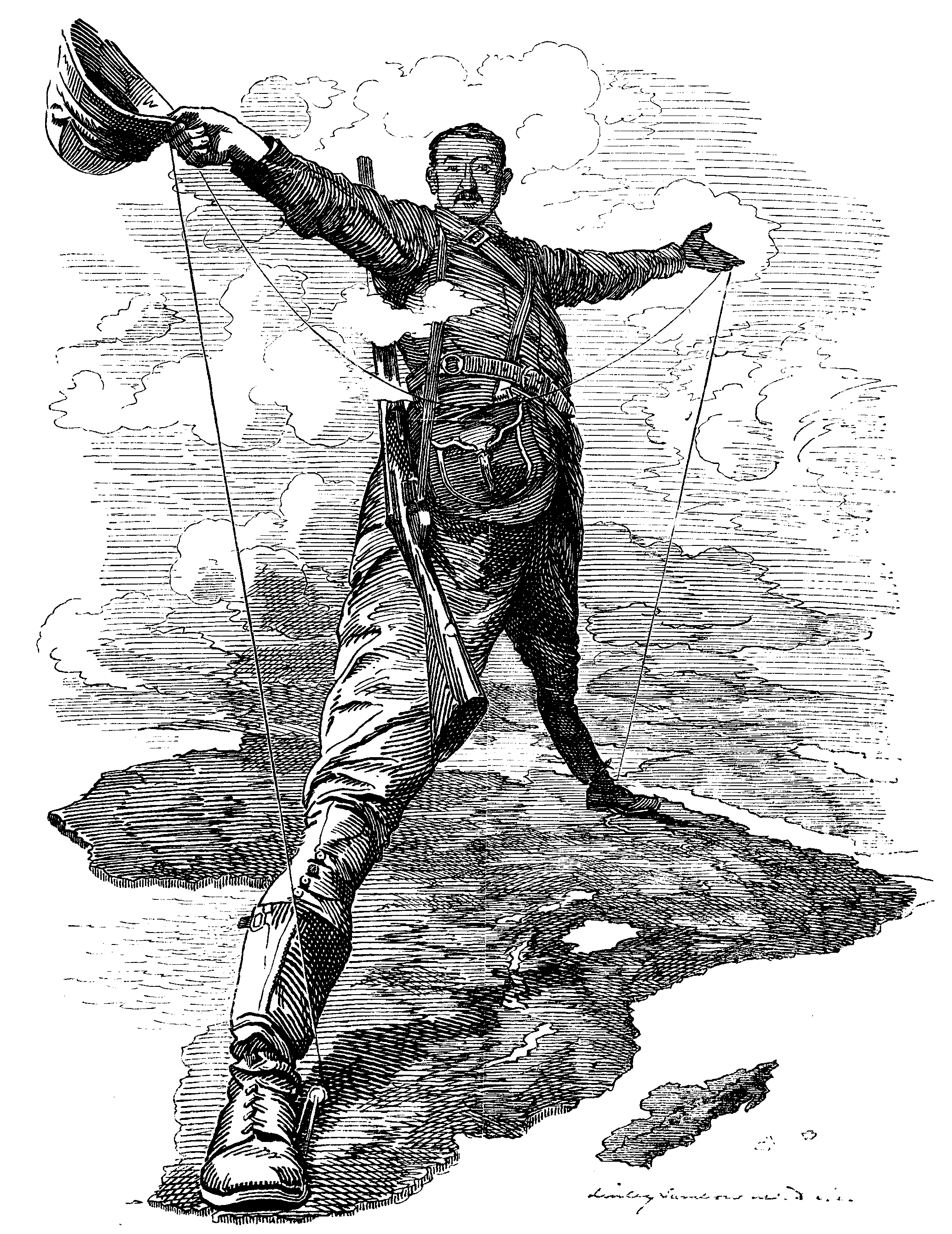

Rhodes, who had become Prime Minister of the Cape Colony in 1890 (he was to serve until 1896) began to associate his push into the new territory with the more grandiose scheme of completing a Cape to Cairo telegraph line and railway. He wrote articles in the British press enthusing about the project and was famously (mildly) ridiculed in a Punch cartoon in 1892.

Through Bechuanaland Protectorate

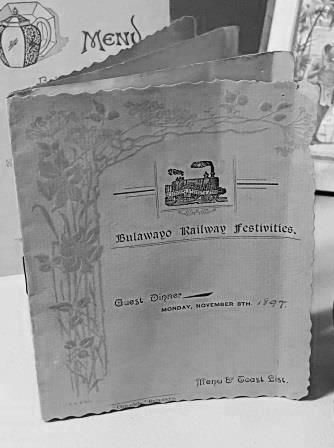

Construction of the railway northwards from Mafeking through the Bechuanaland Protectorate (modern-day Botswana) proceeded at some speed. The line reached Bulawayo in 1897 by which time the BSAC, had supressed a rebellion of the Ndebele and Shona (Second Matabele War, 1896) and established white settlement across much of the area that would become Rhodesia (today’s Zimbabwe).

This section of line was operated by the Bechuanaland Railway which became Rhodesia Railways in 1899. Interestingly, it continued to be run by Rhodesia Railways and then by the National Railways of Zimbabwe right up to 1987, more than 20 years after Botswanan independence. The line is now under the control of Botswanan Railways but as of 2025, all passenger services are suspended.

Into Rhodesia

Even before the railway had reached Bulawayo, thought had been given to what route it might take towards its eventual goal in Egypt. It was suggested that it would head directly north from Bulawayo, pass through the north-eastern part of BSAC’s new “Charter land” (present-day Zambia) and thence into German East Africa (present-day Tanzania) and along the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika. Rhodes made representations to the German Kaiser in Berlin in 1899 but was unsuccessful; a different course through the topologically challenging Belgian Congo (present-day DRC) was eventually pursued.

Meanwhile, another BSAC-sponsored line reached Bulawayo in 1902. It had originated at the port of Beira in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique), had crossed the border at Umtali (Mutare), and had passed through Rhodesia’s eventual capital, Salisbury (now Harare). Situated at the point where the lines from Cape Town and Beria met and combined to push north, Bulawayo now became a very important railway centre and the eventual location for the headquarters of Rhodesian Railways.

Continuining Northwards

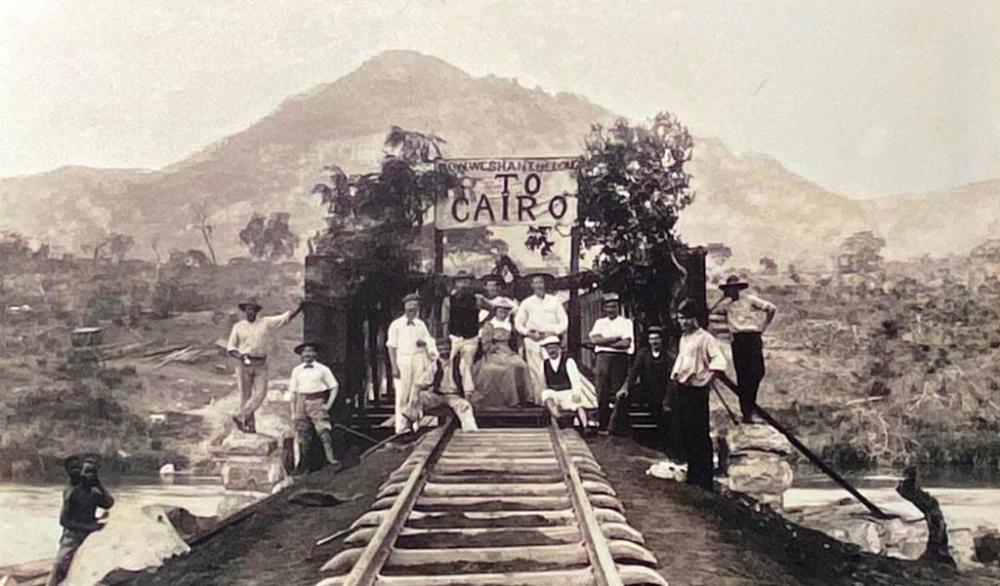

Rhodes died in 1902 and while some of the dream of Cairo died with him, the idea continued to be championed by others, with engineers George Pauling and Charles Metcalfe working on the project until 1914. Yet, the need to find profitable traffic for the railway in the short term soon became a bigger influence on the choice of route than the goal of reaching Egypt.

Extensive coal deposits near Wankie (Hwange) had been discovered and it was decided to abandon the plan to go directly north and head north-west to the coalfield instead. In 1903 the railway was extended to Wankie about 400 km north of Bulawayo. Victoria Falls (just to the north of Wankie) was reached in 1904 and then, after crossing the Zambezi via the famous bridge, the railway opened to Livingstone in 1905.

From Livingstone (in present-day Zambia) construction of the line continued apace; in 1906 it was opened as far as Broken Hill (Kabwe) and by 1909 it had reached Ndola and crossed the border to arrive at Sakania in the Belgian Congo (present-day Democratic Republic of Congo). As the line progressed north, sources of freight traffic were also developed. From the sawmills around Livingstone came lumber and from Broken Hill (Kabwe) came lead.

Having crossed the border a few kilometres north of Ndola, the line headed into the Belgian Congo to pursue potentially lucrative mineral traffic there. It was only much later in the 1920s that copper extraction developed on the Rhodesian (present-day Zambian) side of the border. A network of lines was eventually constructed from Ndola to serve the mines. They passed through Kitwe, now the terminus of Zambian Railway’s passenger operations.

A Dead End – Belgian Congo

From Sakania northwards, now within the Belgian Congo, the line became the responsibility of the Compagnie de Chemin de fer du Katanga (CFK). It passed through the important mining area and town of Elizabethville (present-day Lubumbashi) to reach Tenke in 1914 and was extended to Bukama on the navigable Lualaba River in 1918. Yet, it was not until the late 1920s that the connection was made to Kamina which enabled the line to run though to what would become its ultimate terminus at Kindu (opened back in 1911) or to Albertville (1913) on Lake Tanganyika.

If we consider that the Cape to Cairo line finally ended at Kindu, this still left a gap of 2,000 km to the next section of usable line at Wau in present-day South Sudan. Ironically, by the time the railway had reached this “dead end,” the Germans, defeated in the First World War, had relinquished control of what is now Tanzania, opening up the possibility of an easier alternative route. Poor economic circumstances in the 1920s and 1930s meant it was never seriously considered. After the Second World War decolonisation reduced or eliminated the demand for it altogether.

Alternative Ending 1 – Angola

Begun in 1903 but only opened fully in 1931, the Benguela Railway linked the Portuguese West African (present-day Angolan) port of Lobito with the “Cape to Cairo” railway at Tenke in the Belgian Congo. Also built to Cape Gauge, it became part of a theoretical continuous railway route all the way from Cape Town to Lobito. In reality, it actually acted in competition with the line through South Africa and Rhodesia. By removing the need to travel by ship as far as Cape Town, it provided a shorter access route to the Congolese and Zambian mineral areas for both freight and passengers. When the border was, in theory at least, shut between Zambia and Rhodesia in the early 1970s, traffic boomed.

Alternative Ending 2 – Tanzania

The Tazara Line, constructed by the Chinese in the early 1970s also to Cape Gauge, connected with the “Cape to Cairo” Railway at Kapiri Mposhi and stretched all the way across the Tanzanian border to Dar es Salaam. This effectively created a continuous 3ft 6in system all the way from Cape Town and, by virtue of a north-facing junction at Kapiri, a coast-to-coast route from Dar to Lobito as well. The opening of the Tazara in 1976 enabled Zambia to export its copper via Dar, thus removing the need to use the networks of white-dominated Rhodesia and South Africa and, by then, war-torn Angola.

Legacy

The development of railways in Africa was characterised by lines being constructed primarily to take minerals from the interior to the coast. Individual networks were usually limited to each colony / country. Landlocked countries tended not to develop systems.

The big exception was the 1067mm (3ft 6in) “Cape” gauge system that originated in the Cape Colony and was spurred on initially by Cecil Rhodes. It spread to Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Zambia, later extending to the DRC, Angola, Malawi, Tanzania and also Namibia. The combined total route milage of this network exceeds that of Japan, which with 22,000 km is the largest “Cape Gauge” system within a single country.