Part One

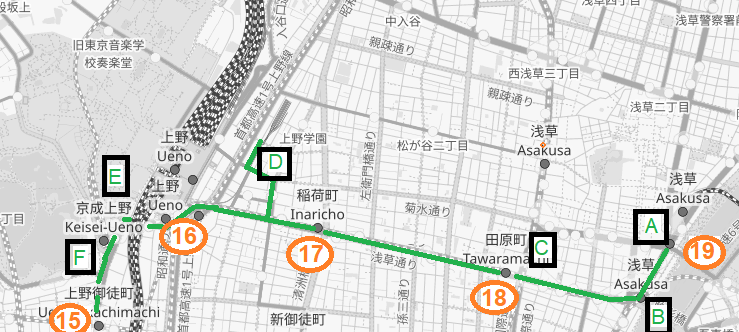

Walk from Asakusa, G-19 (0.0 km)

My walk begins opposite the entrance to the Asakusa Kannon Temple complex. Dating from the 7th Century, although it has been rebuilt several times, this is Tokyo’s oldest Buddhist Temple and one of the most popular draws for foreign tourists in the city. Today it is so crowded I am not even attempting to get close; I am content to stand here on the other side of the road.

The touristy atmosphere here is almost unique in Tokyo. There are English signs everywhere, souvenir shops, places to rent Kimonos and young Japanese guys dressed in old costumes offering rides around the streets in rickshaws. When I lived in Tokyo (1987-1994) I didn’t really like visiting Asakusa, it always seemed to present a false image of “my” city.

Now, as a tourist myself, it doesn’t bother me too much. Although today it is particularly busy and I am keen to be on my way. I walk off heading the short distance to the bank of the Sumida River.

Even before the Meiji period (1868-1912) the area around here had grown into one of the main entertainment areas of Tokyo. As Japan opened up to outside influence in the 1870s, Asakusa developed further. A short distance from the temple I pass Kamiya, Japan’s first Western-style bar. It was opened in 1880 although not in this building.

Kamiya is known for “Denki Bran”, a blend of brandy, wine, gin, vermouth, and herbs. Its electric taste gave rise to its name which translates as “Electric Brandy.” It was invented by the owner of the bar back in 1893. I will admit to never having tasted it.

Asakusa declined after sustaining heavy damage in World War Two and lost prominence as a nightlife hub, but back when the chikatetsu was being planned in 1920, the streets here were filled with bars, theatres and cinemas. It would have seemed the logical place to begin to improve transportation links with the rest of the city.

I reach the Sumida River and look across. The Asahi Beer buildings and Tokyo’s tallest structure, the Skytree (634 metres), dominate the modern scene. Back in 1902, the Tobu Railway, a commuter line, opened its first Asakusa terminal on the other side of this river. The current name of that station, “Tokyo Skytree” give a clue to its exact location.

I turn around to face the Matsuya department store building. Matsuya first opened in 1931 and enclosed inside it was the new Asakusa terminal of the Tobu Line. The suburban railway was extended here over a bridge across the Sumida River. Amazingly the building has survived and is still performing its original function.

This dual purpose building was a novel concept back in the 1930s, it was only later that major stations like Shibuya, Shinjuku, Meguro, and Ikebukuro adopted similar designs, integrating department stores into railway stations to simplify shopping and commuting for suburban passengers.

I have decided that I will visit just one surface entrance for each of the Ginza Line stations on my walk. There are several here at Asakusa to choose from, including a link leading out of the basement of the Matsuya building and a connection from the Toei Asakusa Line which arrived here in 1960.

Undoubtedly, though, the most interesting entrance is this commemorative one built to celebrate the first underground railway in the orient. The station opened on 30 December 1927. In 2004 it received the number G19. My countdown to G1 has begun.

Walk to Tawaramachi, G-18 (0.8 km)

I now endeavour to follow the Ginza Line on the surface calling at all the stations along the route. Initially the line heads south route parallel to the river, so the first part of my walk takes me along the Edo-dori (Edo Avenue). As I walk the tourists drop away and things get quieter.

At 11:58 am on 1 September 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake struck. It killed more than 100,000 people across Tokyo and neighbouring Kanagawa. Much of Tokyo’s Shitamachi (downtown) area, including large sections of Asakusa, was burned to the ground. The reconstruction programme that followed the disaster shaped the modern cityscape. One result was a more planned network of wider main roads, some of which I will be walking along on this trip.

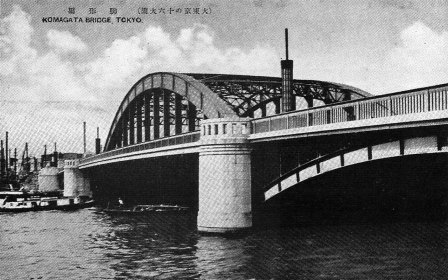

After a short stroll along Edo-dori, I come to a crossroads and, following the subway as it curves east beneath the surface, I turn right into Asakusa-dori. I will now follow it all the way to Ueno. As I turn, I glance towards the river on the left, this is Komagata Bridge. It was built in 1927 in an Art Deco style.

One of the goals of my walk today is to imagine things as they were when the chikatetsu opened and seek out those structures that had only just been built as part of the restoration of the city. The bridge here can definitely go on that list.

Now I start to walk up Asakusa-dori. I am amazed how quickly the neighbourhood has changed. The road is six lanes wide and it stretches in a straight line with tall buildings on either side. The Ginza Line, of course, is running directly below the suface.

I am walking through a residential area. There are no tourists to be seen here despite the fact I am still only a couple of blocks from Asakusa. Almost all the buildings along this stretch are around six stories or taller. They are almost all modern too, there are one or two exceptions, but I am certain there is nothing here from before the war.

A few minutes later, I come to Kokusai-dori. This vibrant thoroughfare stretches several blocks north from here all the way to Minowa. It now claims to be Japan’s longest shopping street. A walk along it would be an interesting trip in itself.

I cross Kokusai-dori and on the other side of the road is an entrance to Tawaramachi, G18, the first station out of Asakusa on the initial section of chikatetsu to Ueno that opened in 1927. The entrance has been modified from its original and now sits underneath the canopy of an arcade.

Walk to Inaricho, G17 (0.7 km / 1.5 km total)

A block further on from Tawaramachi I come to Kappabashidougai street. I now decide to go for a short wander away from Asakusa-dori. The street and the area surrounding it are famous for kitchenware, with shops selling to both the restaurant trade and consumers. I walk past shops busy with customers.

There are places selling pottery and lacquer bowls, others specialising in knives and several selling general items, pots, pans and kitchen implements. Kappabashi is also famous for the plastic models of food items often found in front of restaurants.

All of this trade began after the war. When the chikatetsu opened back in the 1920s this area was just starting out as a place where second hand tools could be bought and sold. Its current function eventually grew out of that.

I set off again on Asakusa-dori still heading towards Ueno in the distance. I glance at a map display and see that there is a sento (public bath) on a side street near my next station. I make a small diversion and head to it.

I find the Hi No De (Sunrise) hot spring around the next corner. I am a little disappointed to see that it is in housed in a modern building, but it is surviving, nonetheless. Back in the 1920s most houses in Tokyo were built without baths and people depended on a visit to the sento.

When I lived in Tokyo in the mid-1980s there were still a lot left. I visited several times. These days they are a dying breed, less of a necessity and more of a luxury, and many are marketing themselves as hot springs like the one here.

There is a picture of how an old sento might have looked on display at the Shitamachi museum in Ueno. There are also a couple of wonderfully recreated dwellings that can be explored inside the museum.

A peep inside gives you some idea of what life in the area I am walking through now would have been like for most people back in the 1920s and 1930s. There is a merchant’s house and a coppersmith’s workshop. Visitors can walk inside and touch artifacts from the Meiji/Taisho eras

Taito City’s Sakamoto area (currently Negishi 3-chome), along Kanasugi-dori Street, which is being recreated at the museum, was spared by the Great Kanto Earthquake and the Great Tokyo Air Raids.

I arrive at my next station, Inaricho, G17. The exits here are on opposite sides of the street separated by direction. The early station design did not include the common entrance leading to both platforms found on later stations. Here there are two separate staircases leading down to either platform.

If you want to go towards Asakusa the entrance on the north side of the street is clearly marked for that purpose, whereas if you are bound for Shibuya you access the line from the south side of the street. There is no connection between the two platforms.

Walk to Ueno, G16 (0.7 km / 2.2 km)

The tall buildings of Ueno are getting closer as I resume my walk along Asakusa-dori. It is busier here too. In quick succession, I pass branches of Japan’s ubiquitous convenience stores, Family Mart, Seven Eleven and Lawsons. There is a McDonalds and a hotel too.

Suddenly in all the modernity I spot a Torii Gate standing by itself. This is the Shitaya Shrine entrance. It dates back to the eighth century. It is a great example of how a walk around Tokyo never ceases to surprise. Right in the centre of the modern 21st century city, something thoroughly ancient suddenly appears.

As if by contrast, just around the next corner some foreign tourists are photographing themselves in front of a bank of five vending machines. I have to admit that the scene is colourful.

I make my way a few blocks north of Akasaka-dori and arrive at the entrance to the Ueno Ginza Line depot. The trains access the depot by a single track that leads up from the running tunnel and there is a level crossing, unique on the system, here so they can cross the road.

Peering through the gate it is possible to see a few of the trains stabled in the yard. The depot has underground storage as well with a total capacity for 20 of the 40 trains that work on the line.

They have protected things well. There are extra gantries here to make sure people are safe when the trains come past, which is presumably mostly in the very early morning and late evening. I peer through the gate down into the tunnel.

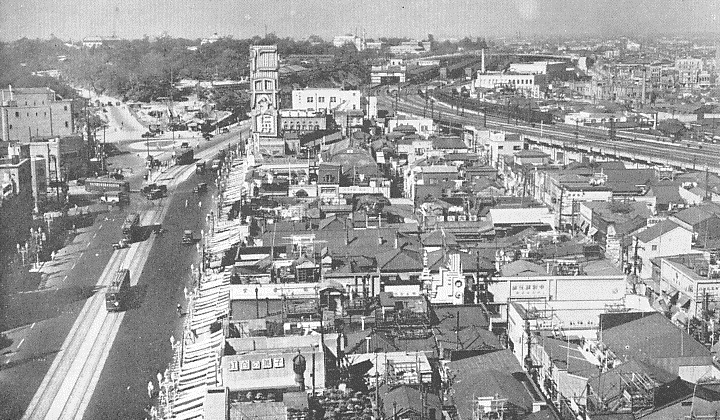

I arrive at Ueno. The busy road junction here means that they have installed a series of linked footbridges which can be negotiated easily to move around above the streets. It is not the most attractive arrangement but it does give me a good view of Ueno station building.

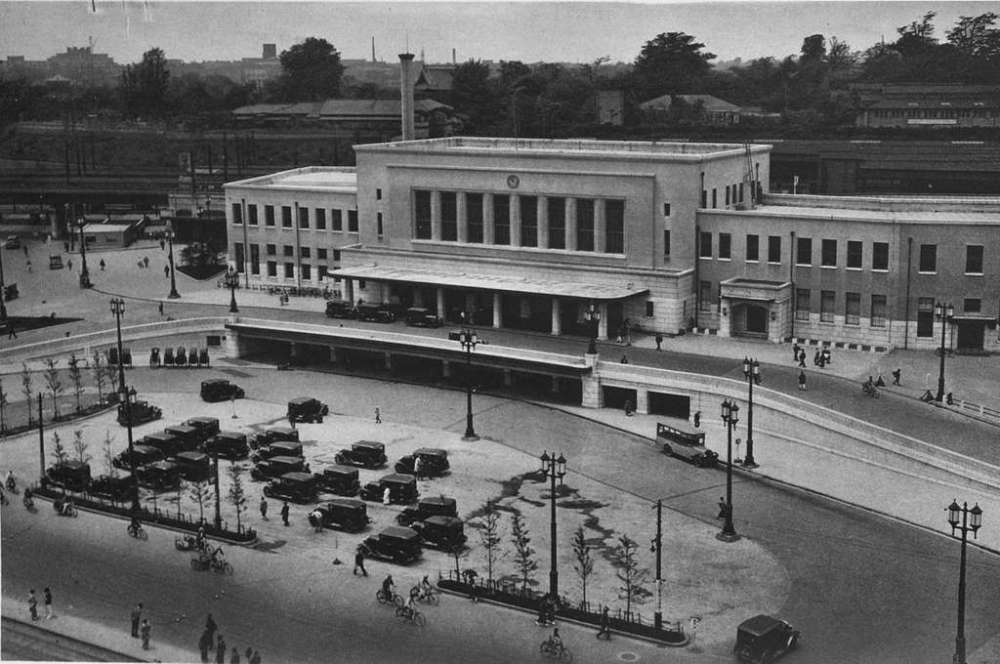

Ueno was the traditional terminus for long-distance trains from northern Japan, although with the extension of the Shinkansen lines to Tokyo Station in the 1990s its role has diminished. The original station building here dated from 1883 but was destroyed in the 1923 earthquake.

Its 1932 replacement is still standing today, a remarkable survivor among Tokyo’s ever changing scene. Although a separate new “park” entrance has been constructed recently, the view that greets me now is not too different from photographs from the 1930s.

One of the entrances to the Ginza Line station is built into the station front and retains its elegant design. The station here opened at the end of the first section of the chikatetsu line on 30th December 1927. Ueno remained a terminus for just over two years. In 1961, the Hibiya Subway Line was constructed to the station.

Walk to Ueno-hirokoji, G15 (0.5 km /2.7 km)

I clip under the tracks at Ueno and come around to the Hirokoji entrance and then cross the road. It is extremely busy now with people pouring out of the station and others milling around the shopping arcades.

I come from under the tracks and emerge on Chuo-dori. Now I am inside the Yamanote loop line. This whole area was a centre of black market activity just after the Second World War.

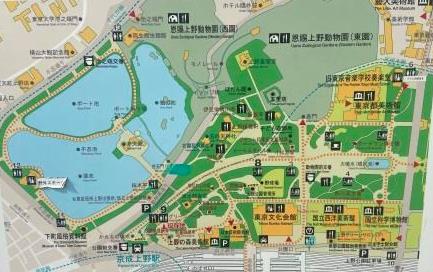

I wander up above the station to enter Ueno Park. The park is known for its museums, temples and Shinobazu Pond. Today it is busy with local and foreign tourists who have come to appreciate the autumn colours. The park is also well known for attracting large crowds in the cherry blossom viewing season.

Back on Chuo-dori, now I am heading south to Ueno-hirokoji. Hirokoji means “wide street” and it first described the broad path that was created here as a fire break after a major conflagration in 1657.

This area was once home to Kaneji Temple and was a significant religious and commercial corridor. It was also here that the remaining group of samurai made their last stand against Imperial forces at the Battle of Ueno in 1868.

Just below here is Keisei Ueno station. I associate it with the fast Skyliner trains which reach Narita Airport in around 40 minutes, but it first opened in 1933 as Ueno Koen Station. The Keisei was one of several such private railways that terminated around the Yamanote Line.

I wander over to the Shizonabu Pond part of Ueno Park. It has three sections, a duck pond, a lotus pond, and a boat pond. Close by is the entrance to the Shitamachi Musuem. It is well worth a visit.

I wander down Chuo-dori passing the Matsuzakaya Ueno department store on the left. It has a very modern facade but it is actually a relic from 1929. Rebuilt after the 1923 earthquake, Matsuzakaya is one of Japan’s historical retailers. This branch introduced “elevator girls” to Japan.

Here I come to the first entrance of Ueno-hirokoji Station, G15. It was opened on 1 January 1930 as part of a three station extension from Ueno southwards. Since 2000 it has also had connections with the nearby Toei Oedo Line station.

Route Map

Continue the walk – G14 to G10