Part Three

Walk to Ginza, G9 (0.7 km / 7.1 km)

Now I come to a second flyover carrying another one of Tokyo’s inner city expressways over Chuo-dori. Kyobashi (Capital Bridge) used to cross a canal here. The waterway was filled in at the time the road was built in the early 1960s.

There are still some things here to indicate what went before though. Just before the flyover is a small garden with several bamboo trees. A few people are sitting around smoking. There is a memorial with some information and photographs.

I learn that the banks of the old canal here were used as a market centred on radish (daikon) in the Edo period (1603-1868). Also known as the “radish riverbank”, it continued on right up until the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923.

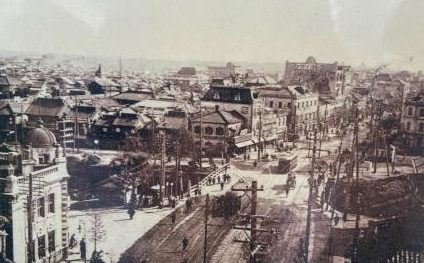

Apparently the south side of the canal was the bamboo wholesalers’ area. It was known as Takegashi (Bamboo Quay). There is a photograph of Kyobashi itself taken in the Taisho era (1912-1926).

On the opposite side of the road here is a modern building housing the Tokyo Police Museum. Then, by coincidence, on the other side of the bridge is a police box or Koban decorated in an old style. These local police points are found all over Tokyo but this is one of the most elaborate I have seen.

Having crossed Kyobashi, I have now passed into a different area. In theory, I am still on Chuo-dori but the street here is better known as Ginza. The word translates as “Silver Mint” and actually refers to the whole area. It originates from the early 1600s when coins began to be produced near here.

The Ginza Line now runs the whole distance underneath the road that gives it its name. This is the equivalent perhaps of Bond Street in London or Fifth Avenue in New York. We start off modestly with a few smaller jewellery shops and foreign bag companies like Tumi and Samsonite.

Then things start to get a little more expensive, and soon I am walking past branches of the world’s most luxurious brands in quick succession. They are all here, Louis Vuitton, Cartier, Tiffany and many more.

Walking down Ginza and looking at the shops was certainly something that would have been familiar to Tokyoites in the 1920s and 1930s. They wouldn’t have been looking at any of these buildings though. All of them are modern and many of them look like very recent additions.

The decade following the Great Kanto Earthquake was known as “the cafe era” in Ginza. In 1922 there were twenty cafes here, by 1929, there were fifty. The cafes were popular with the young “modern boys” and “modern girls” (mobo and moga) as places to socialise. The term Ginbura was a slang word describing strolling around Ginza.

I divert away from my luxury window shopping for a while to visit one of the few structures left from the 1930s. The Okuno Building, located one block to the east, is an early modernist structure. It was originally known as the “Ginza Apartments,” and actually comprises two buildings standing side by side and now coupled together inside.

The main building, on the left as one faces the entrance, was built in 1932, and the so-called “New Building” on the right was completed two years later. The story goes that Okuno Jisuke owned a factory here that was damaged in the Great Earthquake. He relocated afterwards and developed the site into apartments.

The building was made of reinforced concrete, to withstand subsequent earthquakes. Today nobody lives here, but the whole complex has been given over to microbusinesses. I spend quite some time wandering around the six floors peering in to the various craft shops that have been set up in the old apartments. Close by is Renga-tei. It opened in 1895 here in Ginza as a Western-style restaurant. It is known for developing some of Japan’s most famous western-style dishes; tonkatsu (pork cutlet in breadcrumbs), omu-rice (rice omelette) and hashed beef. It is lunch time, so I go inside.

Close by is Renga-tei. It opened in 1895 here in Ginza as a Western-style restaurant. It is known for developing some of Japan’s most famous western-style dishes; tonkatsu (pork cutlet in breadcrumbs), omu-rice (rice omelette) and hashed beef. It is lunch time, so I go inside.

Although it is now in a more modern building the atmosphere feels quite “retro” without being too luxurious. There are old payphones and other artifacts on display. The menu that the formally dressed waiter brings me has the same dishes that it would have had a hundred years ago.

Although it is now in a more modern building the atmosphere feels quite “retro” without being too luxurious. There are old payphones and other artifacts on display. The menu that the formally dressed waiter brings me has the same dishes that it would have had a hundred years ago.  I have encountered omu-rice (tomato flavoured rice in an omelette) and tonkatsu all over Japan and eaten them many times. It is fascinating to think that they were both invented here. The pork is absolutely delicious.

I have encountered omu-rice (tomato flavoured rice in an omelette) and tonkatsu all over Japan and eaten them many times. It is fascinating to think that they were both invented here. The pork is absolutely delicious.

Back on Ginza, amongst all the upmarket boutiques and department stores, there is one outlier. Kimura-ya, widely considered to be Japan’s oldest bakery, was established in 1869. I pop in to get some of their famous anpan, little buns that feature red bean paste. The buns are made using a unique rice yeast (sakadane) which is supposed to make them palatable to the Japanese. I always find them quite delicious. I get a couple and stand munching them whilst people watching on the Sukiyabashi crossing.

The buns are made using a unique rice yeast (sakadane) which is supposed to make them palatable to the Japanese. I always find them quite delicious. I get a couple and stand munching them whilst people watching on the Sukiyabashi crossing.

Sukiyabashi is one of the busiest crossings in Tokyo. On the northwest of the intersection stands one of Tokyo’s most famous landmarks, the Wako Building. The luxury department store was completed in 1932 and then known as the K Hattori Building.

Hattori was the founder of Seiko, the watch company, and the building, in Art Deco influenced style has a clock on the top. It survived the war and was used by US forces as a store during the occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1952. Today it has been renamed after the company’s most famous brand, “Seiko House Ginza.”

On the opposite, northeast corner, Mitsukoshi opened a branch of its department store in 1930. The Ginza location has since undergone several renovations and expansions, including a major rebuilding in 2010 that added a new annex and a rooftop garden.

On the southwest corner of the crossing, I come to one of the exits for Ginza Station, G09, which opened on the Ginza Line on 3 March 1934, more than a year after the line had reached Kyobashi. After the war, the Marunouchi Line began service to Ginza in 1957, and the Hibiya Line platforms opened here in 1964.

Walk to Shimbashi, G-08 (0.9 km / 8 km)

I set off again, walking south on my last leg of Chuo-dori towards Shimbashi. The shops that continue on the south side of the crossing are only slightly less prestigious. I walk past Nissan, Sony and Prada. Then there is a branch of Uniqlo, Japan’s fashion discount store.

Dior, Abercrombe & Firch and Ferragamo and some local companies Yamaha and Shiseido bring me slowly towards the end of the street. There are some stunning buildings here but nothing really old at all.

Ginza starts to fizzle out. I come to another expressway bridge. In a repeat of the scene at Kyobashi, as it crosses Chuo-dori it is following the route of another infilled canal.

The bridge that Chuo-dori would have used to cross that canal was Shimbashi (New Bridge). There is no sign of any water here now. The “Ginza Nine” shopping centre is filling up the space below the expressway.

At the crossroads ahead, I turn right from Chuo-dori into Sotobori-dori. Under the surface, the Ginza line does the same thing, curving to the west to enter Shimbashi station.

As I follow its course, the luxury of Ginza is now well behind me. There is a branch of the Doutor coffee chain, a ramen noodle shop and a Family Mart convenience store. I am now in Shimbashi, which is known as a salaryman’s entertainment district.

There are a lot of office blocks and company HQs around here; the area is full of places that office workers can go in the evening to eat and drink. I walk on, passing under the Shinkansen tracks, the Tokaido Line, the Keihin Tohoku Line and finally the Yamanote Line.

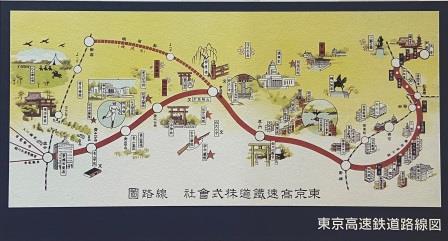

The entrance to the JR Shimbashi Station and the next Ginza Line stop, G08, is on the right here. The line that I have been following from Asakusa (then operated by the Tokyo Underground Railroad Company) arrived here on 21 June 1934. For more than four years it remained a terminus.

Then on 15 January 1939, the Tokyo Rapid Railway (TRR) opened a second subway station at Shimbashi for its own line from Shibuya. After several months, the lines were linked to allow through service and the TRR station was closed. In 1941 the TRR was merged with the Tokyo Underground. The separate Toei Asakusa Line began service to Shimbashi in 1968.

Walk to Toranomon, G-07 (0.8 km / 8.8 km)

Next to this exit of Shimbashi Station is another plaza. It is surrounded by clubs, bars, and restaurants, perfect places perhaps, for the salaryman to inhabit after work. This is SL Square or “Steam Locomotive” Square and it is named for an old engine sitting in one corner.

The locomotive is there to commemorate the beginning of railways in Japan and the surrounding display relates the story of the first line from nearby Shiodome down to Yokohama in 1872. Shimbashi itself opened in 1909 as Kasamori, and the line was eventually extended to Tokyo in 1914.

I continue on my way along Sotobori-dori passing little restaurants, convenience stores, banks and a golf equipment shop. I am walking over the very last section of the Ginza Line to be completed. This is the extension that linked Toranomon, from where the line to Shibuya had already been completed, with Shimbashi.

I cross over Hibiya-dori, one of Tokyo’s busiest north-south thoroughfares. On the other side of the crossing now, the cityscape has changed again. There are more office blocks, fewer shops and restaurants. There are trees lining the road too.

The first two station entrances of Toranomon, G07, appear here. The station opened on November 18, 1938, as the eastern terminus of the Tokyo Rapid Railway from Aoyama-rokuchome (now Omotesando). Trains began running to Shibuya a month later. It became a through station when the line was extended to Shimbashi on January 15, 1939.

Walk to Tameike-sanno, G-06 (0.6 km / 9.4 km)

As I continue on from Toranomon the road winds to the left. This is the edge of the Japanese government quarter, Kasumigaseki. Close to where I am walking are all the various agencies, institutes and ministries that run the country.

At the next corner I encounter a sign with a helpful map telling me where I might find all the various administrative buildings. Here, I am close to the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, the Agency for Cultural Affairs and I am about to walk past the Patent Office. Right in front of me I spot something else.

It doesn’t look much, but the small brick pillar with a plaque in front of me is highly significant to the history of modern Japan. This is the monument, placed here in 1939, to the Imperial College of Engineering. The college was founded in 1873 to train engineers in Western-style methods.

It played an instrumental role in ensuring Japan was able to industrialise quickly. Without it, the country may not have been in the position by 1927 to create its first subway. The original building was destroyed in the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake.

I peer into the National Museum of Territory and Sovereignty on my left. The lady on the reception smiles and beckons me in, but I don’t have time. This government facility is aimed at promoting understanding of Japan’s territorial claims, especially the Northern Territories (disputed with Russia) and Takeshima and Dokdo (disputed with China). I stick it on the list for my next trip.

Surrounded by modern skyscrapers, the 400-year-old Kotohiragu Shrine provides a glimpse into another era. Locals have prayed here since 1660 and nowadays it also draws crowds for its traditional dance performances every month.

I arrive at yet another flyover and here there are also ramps up to the toll booths of the inner city expressway. Off to my left the elevated road follows Roppongi-dori down towards Roppongi, one of the capital’s most dynamic nightlife destinations, and then it continues on towards Shibuya, my ultimate destination.

I go straight under the flyover and on the other side there is the first entrance to Tameike-sanno station, G6. This stop was added to the Ginza Line more recently to provide a changing point with the Namboku Line which arrived here on September 30, 1997.

Walk to Akasaka-mitsuke, G-05 (0.9 km / 10.3 km)

Just a minute’s walk away is a waterfall at the rear of the Japanese Prime Minister’s compound. This area is Nagatacho, Japan’s political heart. The Prime Minister’s office was relocated here in 1929 after the original was damaged in the 1923 earthquake. The building, which has influences of Art Deco and Frank Lloyd Wright in its design, was superseded in 2002 by a new modern office. It is now used only as the Prime Minister’s residence.

In the period from when the chikatetsu first opened in 1927 until its completion in 1939, the job of the Prime Minister of Japan changed as the grip of the military tightened. The office was transformed from a civilian-led role into a position primarily serving Japan’s military-industrial complex and its ambitions of expansion in Asia.

I take a walk around the block and soon come to Nagatacho Ohka, a very exclusive restaurant housed in a 100 year old wooden building. The place used to be a soba (Japanese noodles) restaurant owned by the family of film director Akira Kurosawa. The restaurant is now akin to a private dining club. It has no phone number or website and guests usually need an introduction from a member.

Around the next block is the Diet Building, Japan’s parliament. It was finished in 1936 and, with its central tower measuring 65 metres, then became the tallest building in Tokyo, taking over from Mitsukoshi’s main store in Nihonbashi (See G12). The House of Representatives meet in the south wing (left) and the House of Councillors gather in the north wing (right).

As I walk back towards the subway station, I notice a large police presence. Officers are standing together on the roads and pavements and there are plenty more sitting in buses nearby. I complete a full circle and end up back at Tameike-sanno, passing by the expressway once more as it enters a tunnel taking it under part of the Government district.

A little further up Sotobori-dori there is a massive Torii gate on my right. Leading up from here are escalators and stairs to the South Entrance of Hie Shrine on the top of a hill. I decide to climb up myself to take a closer look.

Although the shrine originates from the Kamakura period (1185–1333), it was moved to its current location by Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate, in the early 17th century.

By coincidence, today is the festival of Shichi-Go-San (Seven-Five-Three), the traditional ‘rite of passage’ celebration for children aged three, five (boys) and seven (girls). The shrine is busy with children dressed in kimonos accompanied by their proud parents.

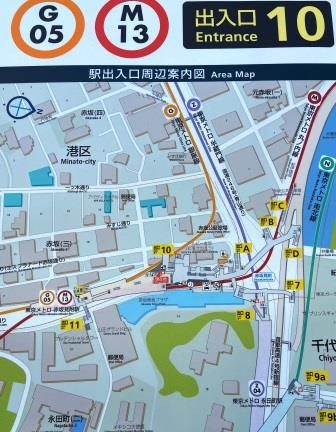

A little further along I find an entrance to Akasaka-mitsuke just on my left. The Ginza Line station opened on 18 November 1938. It was built on two levels with provision for cross platform interchange in each direction with a branch in the direction of Shinjuku.

Construction of the branch was begun in 1942 but soon abandoned. After the war the route was repurposed as the separate Marunouchi Line. The cross-platform interchange finally began operating here on 15 March 1959.

Akasaka-mitsuke is also connected by underground passageways to Nagatacho station, which is served by the Tokyo Metro Yurakucho Line, Hanzomon Line and Namboku Line.

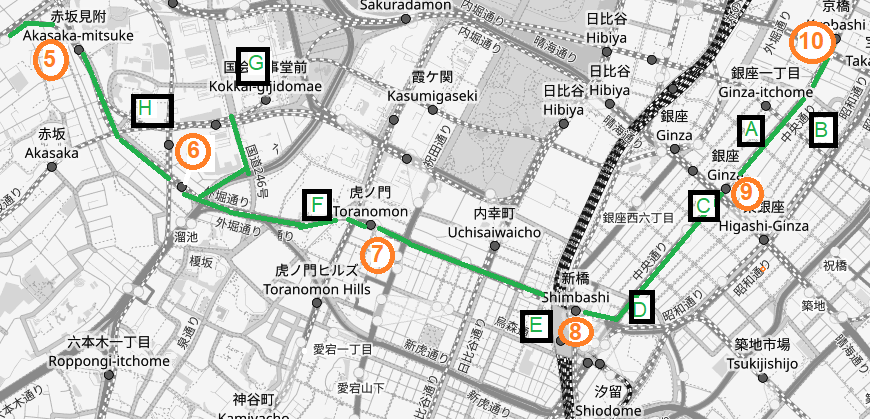

Route Map