A lot has been written over the years about how Japan’s first bullet train line came about. This is my own modest account.

It is a brief look at the events that led up to the opening of the Tokaido Shinkansen on October 1, 1964.

“Tokaido Shinkansen” – Etymology

The literal translation of Tokaido Shinkansen is “East Coast Road New Trunk Line.” The title in Japanese is normally written with six “Kanji” characters and comprises of two separate ideas: Tokaido, an ancient route that came to prominence in the 17th century, and Shinkansen, a term which refers to a concept that originally began in the 1930s: a new trunk railway line linking Tokyo, Nagoya, Kyoto and Osaka.

17th Century – “Walking long distance”

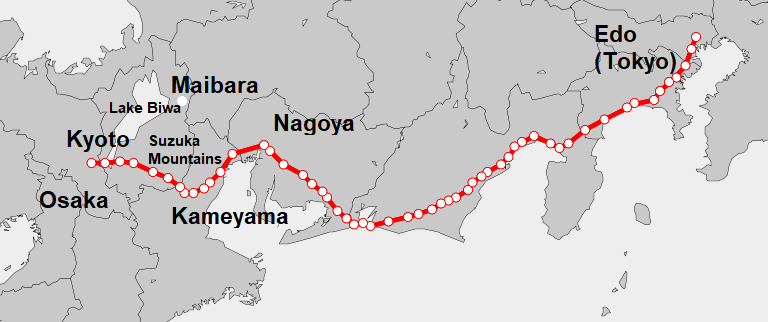

The path that became the Tokaido road dates from ancient times, but it reached its zenith during the Edo Period (1603–1868), when the Samurai dominated Japan. It ran almost 500km from Edo (modern-day Tokyo), home of the ruling Shogun, to the capital city of Kyoto where the Emperor, then merely a token figurehead, resided.

The route, primarily used by travellers on foot, had over 50 “stations” at roughly 10km intervals. Many of these stations later developed into towns and cities that still exist today. West of present-day Nagoya, the road went via Kameyama and through the Suzuka Mountains to reach Kyoto.

1872-1889 – “3 foot 6 inches”

The power of the shoguns ended with the restoration of the Emperor Meiji in 1868. As Japan opened itself up to foreign influence, the capital shifted to Edo and was renamed Tokyo (literally “Eastern Capital”). The country’s first railway was completed between Tokyo and Yokohama in 1872. It was built by British engineers who, for reasons that are not clear, chose a relatively narrow track gauge of 3ft 6 inches (1067mm).

The original line was extended and merged with others until by 1889 Japan had a railway route that linked Tokyo with Kyoto. As far as Nagoya It followed the Tokaido, although until the 7km Tanna Tunnel was opened in the 1930s, it diverted north to avoid the mountains near Atami. West of Nagoya, also in search of an easier path through mountains, it went north towards Gifu through Sekigahara to Maibara, and then headed along the shores of Lake Biwa towards Kyoto. From 1895, the whole line, which also extended westwards to Osaka (destined to become one of Japan’s largest cities) and on to the port of Kobe, became known as the Tokaido Line (Tokaido Sen in Japanese).

1887-1920 “A problem of gauge”

The first idea of a standard gauge (4ft 8.5 inches / 1435mm) railway to link Tokyo with Kyoto and Osaka was mooted even before the Tokaido Line was completed. In fact, the initial notion was actually to convert the Tokaido itself to accommodate wider track and faster trains. As early as 1887 there were calls by the Japanese Army for all railways to look at standard gauge to assist military transportation. A proposal for an investigative committee was passed by the Diet the following year. The issue was eventually overshadowed by debates over nationalisation in the worsening economic conditions of the early 1890s.

The idea of rebuilding to standard gauge was revisited after nationalisation from 1907 onwards, and it was strongly championed by Shinpei Goto (1857-1929), head of Japan Government Railways (JGR), from 1908. Goto fought several battles with the Government over the next decade to try to push for system-wide gauge conversion but was eventually thwarted by political opposition and the poor economic climate after the First World War. He died in 1929, but can be considered, perhaps, a grandfather of the Shinkansen.

1907- “Nihon Electric Railway”

In 1907 Zenjiro Yasuda, (1838-1921) head of the Yasuda Zaibatsu and great grandfather of Yoko Ono, applied for a licence to build a standard gauge electric railway between Tokyo and Osaka. Although all existing steam-operated private main line railways had been absorbed into JGR in 1907, several private electric railways had remained to serve local needs in Tokyo and other major cities.

The proposal, dubbed “Nihon Electric Railway” was for a brand new route featuring trains at up to 80km/h linking the two cities in six hours. Beyond Nagoya the proposed line passed through Kameyama and headed straight to Osaka avoiding Kyoto. If Yasuda had believed his proposed choice of electricity would exempt him from the new Government monopoly on long-distance railways, he was soon proved wrong, and the proposal was quickly rejected.

1924-1928 – “Nihon Electric Railway” (Revival)

The “Nihon Electric” idea was revived in the 1920s prompted by increasing congestion on the Tokaido Line. This time the proposal was made by the management of the Tobu Railway Corporation and discussions progressed to the point where the government considered granting the licence in 1924. Opposition from Kyoto, to be bypassed by the scheme, was strong and it was eventually rejected. It was revived once more in 1928 but again discarded.

1934-1943 – “Asia Express”

By the early 1930s Japan’s empire had expanded from the Korean Peninsula (under Japanese control from 1910) into mainland China. In 1932 the puppet state of Manchukuo was established in Manchuria, setting Japan on a very dark path towards the Sino-Japanese conflict from 1937 and ultimately participation in the Second World War. In the 1930s the fastest rail route from Tokyo to Beijing (Peking) and Europe was by the Tokaido Line to Kobe, onwards along the Sanyo Line to Shimonoseki and thence by ferry to Korea.

The railway systems in Korea and Manchuria had been built as, or converted to, standard gauge and operating them gave the Japanese valuable experience. The South Manchuria Railway (Mantetsu) had been created back in 1906 and Shinpei Goto himself had been its first president. By the mid-1930s the company was operating the fastest train in Asia. The “Asia Express” ran between Dailan, the Manchukuo capital of Changchun and Harbin. It reached speeds of 135km/h.

1939-1944 – “Dangan Ressha / Bullet Train”

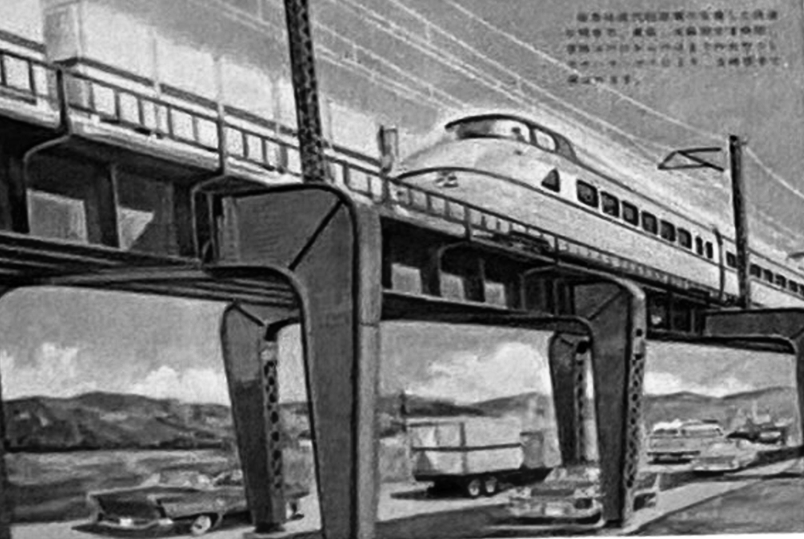

Back in Japan, traffic volumes on the Tokyo to Shimonoseki section grew throughout the 1930s and by the end of the decade capacity was becoming a real issue. In December of 1938 the government established committees to survey and investigate the problem, and in November 1939 the decision was made to create a separate standard gauge trunk line from Tokyo to Shimonoseki. The line would be operated partly by steam, but a large section would be electrified using a 3,000V DC overhead system. Speeds on the electric sections would reach 200km/h. Overall times from Tokyo to Osaka of four and a half hours and to Shimonoseki (984km) of nine hours were forecast.

The project was officially called “Broad Gauge Trunk Line” but was also referred to as “New Trunk Line”, or Shinkansen, the first time the phrase had ever been used. In newspapers and among the public the project soon gained the popular name “Dangan Ressha” literally “bullet train.” Construction began in 1940 with completion forecast for 1954. It was planned that the eastern section of the new line would run broadly parallel to the Tokaido Line but between Nagoya and Kyoto it would avoid Maibara and be routed via the Suzuka Mountains.

By the time the project was cancelled in 1943, due to the deteriorating war situation, land purchases (often forced) were well advanced on the Tokaido section. Among the tunnels that had been started was the longest, Shin Tanna, of which 2km of 7km had been dug, and the Higashiyama in the Kyoto area. The former was eventually completed for the 1964 project, although the latter was not. Another tunnel, the 2.2km Nihonzaka, west of Shizuoka, had actually been finished and in the aftermath of the war it was converted for use by the parallel Tokaido Line for more than a decade, before eventually being given back for use as part of the 1964 project.

When the Shinkansen project was revived in the 1950s, the name Dangan Ressha wasn’t. To this day, it is only ever used to describe the 1940s plan and is a term unknown to the majority of Japanese people. Curiously, though, its English translation “Bullet Train” was used, it lingered and became the most common unofficial way of describing the Shinkansen in English.

1946 – “Japan Railway Company”

The first plan to revive the Shinkansen idea came as early as June 1946 when a project using foreign capital to establish a private company was proposed. The scheme embodied most of the 1940 plan, although, with the need to connect to Korea diminished, the western terminus was shifted from Shimonoseki to Fukuoka. Perhaps unsurprisingly, reconstruction of the existing network from the damage it had sustained in the war was prioritised and the project was quickly discarded.

1949 – Japan National Railways – Engineering Developments

In 1949, at the behest of US General HQ, Japanese Government Railways was reorganised into Japan National Railways (JNR). This public corporation (known as Kokutetsu in Japanese) would remain in place until privatisation in 1987. In the near 40 years of its existence, it would oversee the recovery of Japan’s network from the devastation of war and guide transform itself into a world leader in railway technology.

![]()

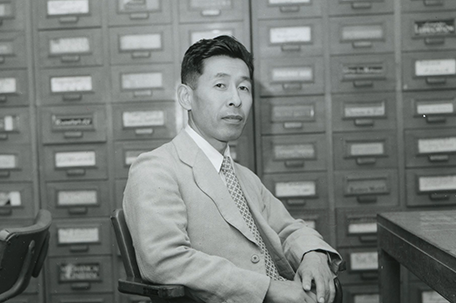

Although the Railway Technical Research Institute (RTRI) had been formed back in 1907, it began to prosper under JNR as it benefited from the arrival of talented young engineers many of whom had been working on military projects until 1945. Chief among them was Hideo Shima (1901-1998) who was to become instrumental in the development of the Shinkansen.

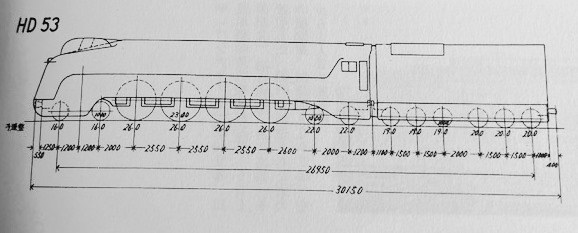

Shima, son of a renowned railway engineer who had also worked in Manchuria, had joined JGR back in 1925 and had been employed in designing steam locomotives including the HD53 proposal for the Dangan Ressha. He became involved in army truck design during the war, but returned to the railway afterwards, becoming head of rolling stock design in 1948. He resigned from JNR in 1951 to take responsibility for an accident but returned in 1955.

Among his postwar creations was the C62 class of steam locomotive which would haul expresses on the Tokaido Line in the early 1950s and set a record of 129km/h for 3 foot 6 inch gauge steam locomotives.

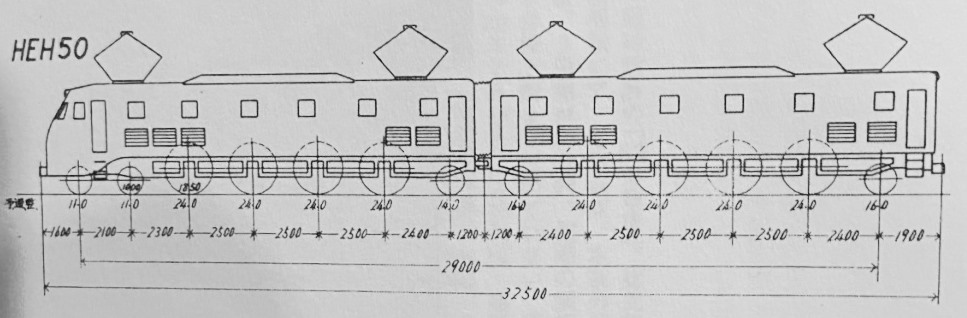

However, Shima’s biggest contribution was in promoting the move away from locomotives. Japan’s narrow gauge system limited locomotive size and power, and as the railways turned away from steam, Shima promoted multiple unit railcars with the power distributed throughout the train as an alternative solution to diesel and electric locomotives. The 80 Series, first introduced in 1950 and used for medium-distance services on the Tokaido line, were an early example.

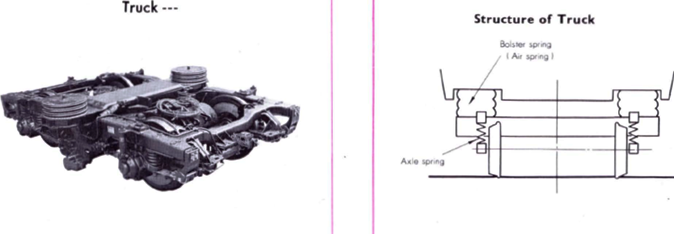

In tandem with the move to distributed power, were developments on bogie design led by Tadashi Matsudaira (1910-2000), a former aircraft engineer who used his experience from stabilising the wings of fighter planes to research the problems that caused railway vehicles to derail. He came up with new bogie designs to counteract issues such as hunting oscillation, the swaying movement of a train at speed.

Another ex-aircraft engineer, Tadanao Miki (1909-2005), also played a critical part in the research efforts, becoming the head of the Vehicle Structure Laboratory and eventually designing the iconic streamlined Shinkansen driving vehicle.

An early culmination of research and design efforts came in 1958 with the introduction of the Class 151 (originally designated Class 20) long-distance electric multiple unit trains on the Tokaido Line. Marketed as Kodama (Echo) they cut the Tokyo to Osaka transit time down to 6 hrs and 30 minutes, their smooth ride and air conditioning ensuring popularity with passengers. Although the trains were limited to a service speed of 110km/h they were tested at over 160km/h and can be considered a precursor of the Shinkansen.

1955 – “The Father of the Shinkansen”

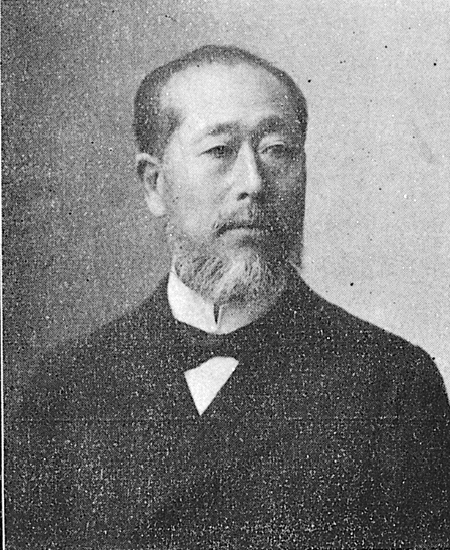

The appointment of Shinji Sogo (1884-1981) as President of JNR in 1955 was a crucial turning point in the decision to build the Shinkansen. Without him, it is easy to imagine that the line might never have been built. Sogo had worked with Shinpei Goto in the 1920s and had been deeply influenced by his ideas for standard gauge as a solution. Sogo was a gifted leader described as tenacious, obstinate and determined. He had a talent for getting around obstacles.

One of Sogo’s first actions was to try and recall Hideo Shima. Reluctant at first, Shima eventually came back to JNR. Understanding the necessity of research and development, Sogo pushed hard for better conditions for his design teams eventually rehousing many of them in a centralised facility.

1956-1958 : “Making the Decision – Committees and Conferences”

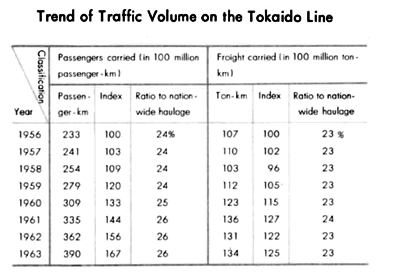

Sogo’s appointment coincided with problems of saturation on the Tokaido Line. Electrification would be finally completed in 1956 but the line was already struggling with 120 passenger trains and 70 freight trains a day against a theoretical capacity total of 120. Although it only represented 3% of the total system it was carrying around 25% of all traffic. Moreover, boosted by Japan’s remarkable economic recovery, with 40% of the population and 70% of the country’s industrial output now located between Tokyo and Osaka, it was experiencing a yearly increase of 8% in passengers and 5% in freight.

In 1956 a committee was set up by the Ministry of Transport to discuss the problems of capacity. Sogo quickly became a fierce advocate of building a new standard gauge line. Yet, his preferred solution was not seen as an obvious one, adding extra tracks to the existing line or building a completely new narrow gauge line were both considered as potentially better options. They both had the advantage of offering compatibility with the rest of the network. They could also both be completed in stages whereas a new standard gauge line would have to be attempted almost in one go.

In May 1957, whilst the committee were still deliberating, the RTRI held a conference in Tokyo to celebrate its 50th anniversary. The chosen subject was “Tokyo to Osaka in 3 hours by train.” Miki and his fellow engineers delivered lectures to demonstrate their confidence in their own ability to create a standard gauge railway that could deliver the commercial speeds necessary to combat the growing threat from the developing Japanese expressway network. The idea of promoting speed in addition to capacity began to catch on.

Finally, in July 1958 the committee delivered its verdict to the Minister of Transport. It would recommend that a new standard gauge line should be built. Its reasons in retrospect sound obvious; larger transport capacity, shorter travel time, safety at high speed, lower funding requirements, possibility to modernise further and use of advanced technology. Sogo had won the argument.

The committee also set a target for passenger trains to complete the journey between Tokyo and Osaka in 3 hours and for trains carrying freight to take 5.5. Carrying freight, primarily at night, remained a goal all the way up to opening in 1964. It was quietly dropped once it became clear that the plans were not economically viable and that all-night possessions would be needed to do maintenance.