A lot has been written over the years about the history of Dutch railways.

This modest attempt aims to provide only a basic introduction to the subject and is illustrated mainly by photographs of the exhibits at the National Railway Museum in Utrecht

Spoorweg Museum

Maliebaan

The Spoorweg (Railway) Museum actually dates from the 1920s but since 1954 it has been located in Utrecht in and around Maliebaan Station.

The main building of the station, which opened in 1874 but closed in 1939, has been beautifully restored and sports marble floors and chandeliers. There is the opportunity to wander through its waiting rooms and glance into a restored barber’s shop.

Outside on the old main platform are a few locomotives and a fascinating collection of carriages from various eras of the Dutch Royal Train, all of which can be walked through.

The second platform is actually still in use and hosts the hourly ‘Sprinter’ shuttle from Utrecht Centraal, whilst a third platform is being used to stable a locomotive and a couple of older electric multiple unit trains.

Scattered around the surrounding sidings are more locomotives and electric and diesel multiple unit trains. There is also a turntable with a collection of diesel shunting engines and an old signal box to explore.

The main collection, however, is housed in an extensive new building dating from 2003. It is divided up into several themed “worlds” of which the largest is “The Workshop”, this comprises most of the main hall which is full of trains.

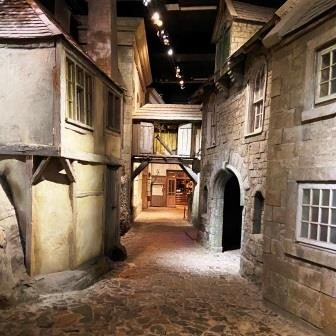

“The Great Discovery” looks back to the early years and includes a simulated trip back to an early 19th Century street in north east England where the first Dutch steam locomotive was designed.

“Dream Travels” incorporates live theatre performances to tell the story of the glory days of international trains around 1900. “Steel Monsters” involves an innovative indoor roller coaster style ride (in little carriages seating four) around several locomotives from the 1930s and 1940s.

The whole thing comes together well. It is informative and entertaining at the same time, and it would seem to appeal to all ages. It is certainly worth a visit.

A Brief History

1839-1859: The First Lines

The Netherlands was relatively slow in constructing its railway network. It needed the intervention of King William (1815-1840) to push the government to contribute funds and encourage businessmen to create the companies necessary to build the lines. Over the first twenty years, two companies were to dominate.

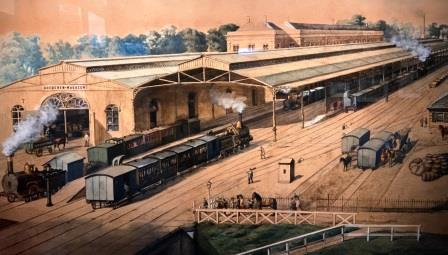

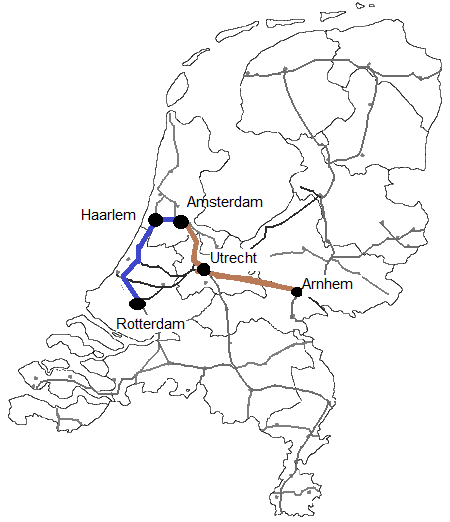

Hollandsche IJzeren Spoorweg Maatschappij (HSM), was founded in 1837 to construct the first line. In contrast to neighbouring countries, it chose a broad gauge of 1,945 mm (6 foot 4 9⁄16 inch). On September 20, 1839, the first train, drawn by British-built De Arend, made the 16 km (9.9 miles) journey from Amsterdam to Haarlem.

Once this first short section proved viable, HSM began to construct southwards towards Rotterdam via Leiden, Den Haag and Delft. Completed throughout in 1847, the route still exists and is known as the ‘Oude Lijn‘ / ‘Old Line’ today.

The second major railway company of the time was NRS (Nederlandsche Rhijnspoorweg-Maatschappi). The name roughly translates as ‘Dutch Rhenish Railway’ and its plan was to build from Amsterdam to Utrecht, Arnhem and then into Germany. Surprisingly, it also used the 1945mm gauge even though the railways of Germany were already being constructed to the standard 1435mm (4 feet 8 1⁄2 inch) gauge.

The NRS line opened to Utrecht in 1843 and to Arnhem in 1845. Yet it was not until 1856, and unsurprisingly not until the gauge of the whole line had been changed, before it reached Germany.

Whilst HSM and NSR were the dominant players, other smaller companies were also building lines. Nevertheless, progress was extremely slow and by 1860 only 325km (202 miles) of railway had been constructed. This compared with the more than 10,000 miles completed in Great Britain by that time.

1860-1899: Government Intervention

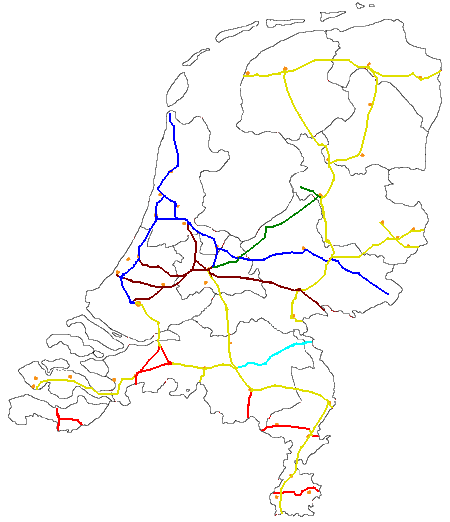

In 1860 the government stepped in to accelerate the construction of lines. It established a plan to create a series of so called ‘state lines’ (staatslijnen) to serve the towns and cities, mainly in the north and east of the country, that the commercial companies had not yet linked to the network.

Although this new network was constructed by the state, the private entity Maatschappij tot Exploitatie van Staatsspoorwegen (Company for the Exploitation of the State Railways) or simply ‘SS’ was founded to operate the trains on it.

This new system used standard gauge from the outset and its development coincided with the final conversion of the original HSM line from broad gauge. The “old line” from Amsterdam to Rotterdam via Haarlem was converted in 1866. Sadly, no broad gauge steam locomotives were preserved and so the oldest surviving engines in the country only date from the mid-1860s.

Other companies that built significant stretches of lines included NCS (Nederlandsche Centraal-Spoorweg-Maatschappij) whose line from Utrecht to Zwolle opened in the mid-1860s, and NBDS (Noord-Brabantsch-Deutsche Spoorweg-Maatschappij), also known as the ‘German line’, whose cross-border line opened in the 1870s.

By the mid-1880s 2,610 kilometres of track had been completed and the network had spread to cover most of the country. By 1900 it was all but complete. Consolidation of the companies occurred from 1885 onwards with NRS first acquiring the shares of NCS and then itself being taken over by SS in 1890. Eventually, only SS and the original HSM remained.

1900-1940 : Modernisation and Unification

The first few decades of the Twentieth Century saw Dutch Railways experiencing growth but also facing serious challenges. Steam-hauled trains got faster and more comfortable. An increasing number of cross-border international services were also operating.

Some, like the Étoile du Nord (Amsterdam to Paris) and Edelweiss (Amsterdam to Lucerne), used the luxury coaches owned by the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (CIWL). The interwar period represented something of a golden era for the company.

Although the Netherlands remained neutral during World War I, the country experienced a serious economic downturn as a result of the conflict. This in turn severely affected the financial positions of both HSM and SS.

In 1917 the two companies took the decision to completely integrate their operations. They remained separate corporate entities but implemented joint initiatives such as unified timetables and common locomotive numbering.

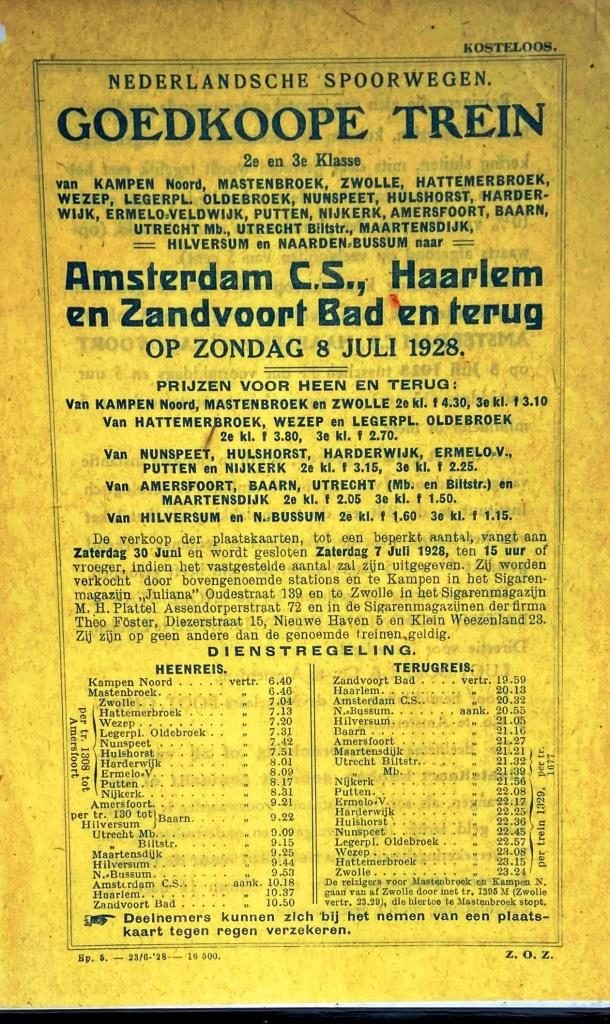

Years in advance of the actual merger, some of their marketing used the title Nederlandsche (an older form of the current Nederlandse) Spoorwegen (NS) translated as ‘Dutch Railways’. The government bought shares in both companies.

Work to electrify the Dutch network began at the beginning of the 20th Century. The first electric line in the country was actually built by the small ZHESM (Zuid-Hollandsche Electrises Spoorweg-Maatschappij) company. It linked Rotterdam with Den Haag and used a unique 10 kV 25 Hz system. Its Rotterdam terminus at Hofplein station gave the line its name, Hofpleinlijn.

In the years following the First World War, the Dutch government established a committee on rail electrification and it concluded that the best system to adopt would be the 1500V DC system. The Hofpleinlijn, having been acquired by HSM in 1923, was soon converted to the standard voltage.

Work on electrifying the old HSM line between Amsterdam and Rotterdam was completed by 1927. The Mat’24 trains built to run on the line were nicknamed ‘Blokkendoos’ (‘box of blocks’) as a result of their sturdy construction.

By 1938 electrification had reached from Amsterdam to both Eindhoven and Arnhem. A new breed of streamlined electric trains, Mat’35, Mat’36 and Mat’40, were introduced for the new services.

Despite technological progress, the late 1930s saw the railways still struggling financially, particularly in the face of increased tramway and motor competition. In 1938 the Government bought all the remaining shares in HSM and SS and merged them to finally officially form NS (Nederlandse Spoorwegen).

1940-1945: War

During the German invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940, the Dutch railway system was impacted significantly. The network was used by the Germans for their military advance and later for the transportation of Jews and other persecuted minorities to concentration and extermination camps.

After the Allied invasion of Europe in June 1944, resistance among railway workers grew and eventually led to the railway strikes of September 1944, called by the Dutch government in exile in London. As a consequence of the strikes over 30,000 railway workers went into hiding.

The final months of the war left the network in a terrible state. By May 1945 more than 200 bridges had been destroyed, various items of rolling stock had been damaged or lost and around 60% of routes were inoperable.

Following the German surrender in May 1945, British War Department locomotives, were used as part of the rebuilding efforts and in the transportation of vital supplies to various parts of the country. Some of these locomotives were eventually sold to NS and continued to serve for a number of years.

‘Tommy and Friends’

There are two exhibits at the museum which commemorate the link between the electrification of the Manchester to Sheffield ‘Woodhead’ line in the UK and Dutch Railways.

Work by the London North Eastern Railway (LNER) to wire the Trans-Pennine route (using the same 1500V DC system as Dutch Railways) had begun before the Second World War but progress had been halted by the outbreak of the conflict.

A single prototype locomotive, LNER 6000, designed by Sir Nigel Gresley, had been unveiled in 1941. At the end of the war, work on the electrification was slowly resumed, but the necessity of building a replacement Woodhead Tunnel meant that it could not be completed before 1954.

The prototype locomotive thus became temporarily surplus to British requirements just at a time when the Dutch were short of motive power. It was transferred to the Netherlands in 1947 and remained there until 1952. It gained the nickname ‘Tommy’ during its stay. British Railways (BR) formalised the name on its return. 57 more locomotives were eventually built between 1950 and 1953 to a slightly modified design and, with Tommy, they became Class 76. Tommy (by then BR 26000) was scrapped in 1970 but one Class 76 was preserved and is currently at the NRM, York.

Meanwhile, seven larger and more powerful locomotives were constructed (1953-4) for the Manchester to Sheffield passenger services. They were numbered 27000-6 and named after Roman and Greek Gods. They eventually became BR Class 77. Yet with BR having moved away from 1500V DC in favour of the 25kV AC system in the mid-1950s, and with the impending withdrawal of passenger services on the Woodhead line in 1970, they soon became surplus to requirements.

In 1968 all seven were sold to NS. One was broken for spares and the other six were renumbered 1501-6 (they kept their names) and put to work hauling passenger and freight trains in the Netherlands. They remained in service until 1985. Three of them have now been preserved. 27000 (1502) ‘Electra’ is now back in its original British Rail colours at Butterley, UK, whilst 1505 (27001) ‘Ariadne’ is still in NS livery in Manchester. 1501 (27003) ‘Diana’ has remained in her ‘second home’ and is on display in Utrecht.

1946-1967: Post-war recovery

With the help of the American Marshall Plan, NS began to rebuild its system from the devastation of war. Most of the main network was electrified whilst new diesel trains were introduced on rural lines. The last Dutch steam locomotive ran in service as early as 1958, a full ten years before its counterpart in Great Britain.

In the early postwar years NS bought electric locomotives of various types in relatively small quantities. From Switzerland in 1949 came ten Class 1000s designed by SLM, and then from 1950 onwards came sixty Class 1100s produced by Alstom in France.

The American company Baldwin designed the Class 1200s of which 25 were built. They were put together locally at Werkspoor with some of the parts designed by Westinghouse and produced in the Netherlands and others obtained directly from the USA as part of the Marshall Plan.

Finally in 1952, again from Alstom, came sixteen Class 1300s. Their design was based on the SNCF Class CC 7100, the type that would go on to set a world rail speed record of 331 kilometres per hour (206 mph) in 1956.

By the mid-1960s the vast majority of passenger services were formed by electric multiple units. The initial postwar design, Mat’46 (built between 1949 and 1952) was based on the prewar streamlined trains. It gained the nickname “Mouse Nose” as the front end seemed to resemble the rodent and in one livery variation even sported whiskers.

The later Mat’ 54s, introduced from 1956, had better protection for the driver built into the design. Because of the large bulbous front and ‘drooping’ side windows they became known as ‘Dog’s Heads’. The Mat’64s (built 1964-1976) followed a similar design pattern but were christened “Ape’s Heads” as a result of their own distinctive front ends.

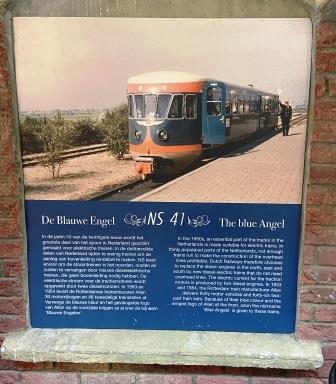

NS introduced diesel multiple units on lines not yet electrified. The DE1 single car and DE2 twin car units (dating from 1954), nicknamed ‘Blue Angels’, were introduced on low profit railways in sparsely populated areas and helped to save many such lines.

The DE3 units (introduced in the early 1960s), resembled the Mat’64 ‘Ape’s Head’ electric trains and were used on regional services. They were known as “Red Devils” on account of their livery.

NS also developed the DE4 jointly with the Swiss (SBB) for the Trans European Express (TEE) network. These four-coach sets dating from 1957 were designed for luxury, first-class travel between major European cities such as Amsterdam and Zurich. After withdrawal in the mid-1970s they were exported to Canada.

By the late 1960s NS was experiencing more competition from the roads. Its image, partly represented by a wide variety of liveries, was seen by many as bureaucratic and old fashioned. The company was influenced by the 1965 rebranding of British Rail and sought to do something similar.

1968-1994: A New Identity

In 1968, NS implemented a corporate identity plan that included a new logo, a distinctive yellow livery, and a series of standard pictograms for stations. The logo featured a widened N and a reverse S and, like its British Rail equivalent, two arrows and two lines representing movement and tracks.

Faced with falling revenue, particularly due to the loss of freight traffic, the company came up with ‘Spoorslag 70‘, an ambitious plan to bring more passenger traffic to the railways. The plan was partially successful, traffic did grow but only as a result of a significant increase in train mileage. Deficits continued and needed to be covered by the state.

The ‘Spoorslag 70’ timetable saw stopping trains and express trains separately branded as “Stoptrein” and “Intercity” respectively. At first the faster services used the existing trains such as the Mat 54s, but in time dedicated units were constructed. The first prototype of the ICM (Intercity Material) emerged in 1976 and production began in 1983 and lasted until 1994. These trains were known as ‘Koploper’ or ‘walk through heads’ given that the design, with a raised driver’s cab, enabled passengers to move between two units coupled together.

In 1977 NS opened the first stretch of railway line built since the Second World War. The Zoetermeerlijn initially connected The Hague and the nearby new city of Zoetermeer. A new type of train, the SGM, was first introduced with the new line. Produced between 1975 and 1983 and known as the ‘Sprinter’ its introduction enabled many older EMUs to be withdrawn. In time the ‘Sprinter’ designation was applied to the type of service, eventually replacing ‘Stoptrein’. The last SGM was retired in 2021.

The network expanded again in 1978 with a new line reaching Schiphol Airport from Leiden and extending to the southern outskirts of Amsterdam. The mid-1980s saw that railway reach Amsterdam Centraal and new lines also built to serve Lelystad, a city that had been built on the reclaimed seabed of the former Zuiderzee.

The 1980s also saw the replacement of earlier types of electric locomotives. Fifty eight Class 1600s were built by Alstom between 1981 and 1984 with ‘Nez Cassé’ (broken nose) styling, and many examples are still in use on freight services today.

The eighty one Class 1700 locomotives, built between 1990 and 1994 were essentially more advanced versions of the 1600s and were often paired with double deck coaching sets operating in push pull mode.

1995-2025 – Splitting up Tasks

In 1995, in line with EU Directive 91/440 which required that infrastructure and trains were managed independently, NS split itself into separate ‘task organisations,’ Railinfra management, Railned and Rail Traffic Control. The freight operation, NS Cargo, was merged with DB (Deutsche Bahn) and operated as Railion from 2000

A system of concessions aimed at introducing more competition has also been introduced. Although state-owned NS remains the primary operator of the main rail network, other private companies like Arriva go through a tendering process to be awarded regional train service concessions.

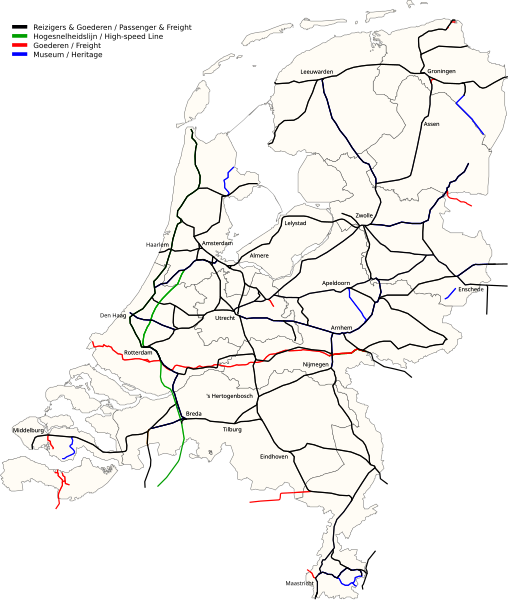

The network has expanded again in the 21st Century with three major additions. The 78km High Speed HSL-Zuid, (shown in green above) stretches from Schiphol to the Belgian border, with a short break either side of Rotterdam. It was opened in 2009 and now hosts Eurostar trains heading for Belgium, France and the UK as well as domestic ‘Intercity Direct’ services. The Hanzeliin (2012) now offers another connection for Lelystad, whilst the Betuweroute (2007) is an east-west freight-only route (shown in red above) linking the North Sea with the German border.

Today the Dutch Railway system extends to around 3,225 km and carries around 1.3 million passengers a day. Those figures are both around a third of the British equivalents. This must therefore be seen as impressive given that the population of the Netherlands is only around a quarter that of Great Britain.